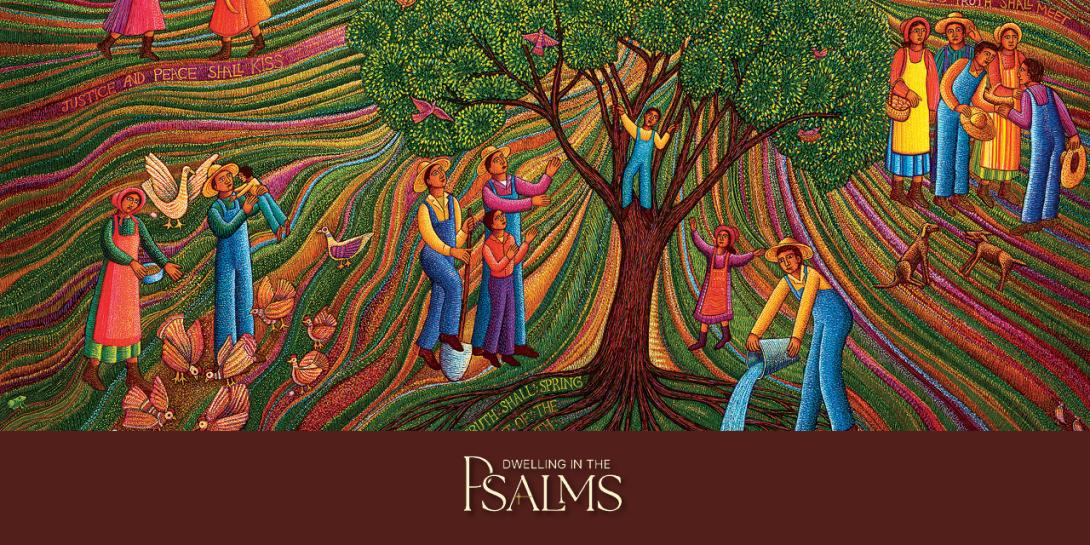

One of my all-time favorite Garrison Keillor monologues on his Saturday-night radio show, Prairie Home Companion, depicts a Thanksgiving Day service at the Lutheran church in quaint, fabled Lake Wobegon. Worshippers, one and all, have brought along bountiful sacks of produce from their household gardens, and the table in the narthex is laden with impossibly red radishes, fresh green cucumbers, brilliantly orange carrots, plump watermelons, deep purple beets, and beans of myriad varieties and colors. It’s a dazzling cornucopia of the year’s harvest to be shared among the worshippers—among the entire community really—for the whole town has gathered to give thanks.

As the service is about to begin, a low but incessant hum breaks forth. Puzzled, the worshippers cup their ears to hear more intently. Then, turning to one another and breaking forth in smiles prompted both by bemused curiosity and wide-eyed wonder, they discover that the vegetables, fruits and flowers have joined together, in joyful harmony and rhythm, to cluck and squeal, to clap and wave the invitation hymn “Come Ye Thankful People Come.” Doing so, adds Keillor, these wonderful creatures from the garden, whom their Maker has brought to full maturity and bloom, are now taking up their God-appointed task of bidding the women, men and children in the sanctuary to join them in a swelling chorus of thanks to the God who created them all.

Earth’s teeming creatures—light, waters, winds, donkeys, birds of the air, mountains, grass, wine, oil, bread, Lebanon’s cedars, storks, crags, coneys, moon, Leviathan, and a thousand others (cf. Psalm 104)—incessantly do sound forth their Maker’s praise. They are calling us to join the cadence of wonder and praise.

Do you picture John Calvin as a fusty, never-smiling, joy-smothering theologian? If so, read his lyrical testimony on creation’s beauty, and think again.

“It is evident that all creatures, from those in the heavens to those under the earth, are able to act as witnesses and messengers of God’s glory … For the little birds that sing, sing of God; the beasts clamor for him; the elements dread him, the mountains echo him, the fountains and flowing waters cast their glances at him, and the grass and flowers laugh before him.”

He adds: “There is not a blade of grass, there is not a flower in the field that is not intended for us to rejoice.”

Commenting on Calvin’s thoughts, Ford Lewis Battles noted: “In the vast theater of heaven and earth the divine playwright stages the ongoing drama of creation, alienation, return, and forgiveness for the teeming audience of humanity itself.”

To see God at work in creation takes careful looking and listening—careful touching, tasting, and smelling too. One’s mind and heart have to be wide-open to welcome messages from the One who “makes the winds as his messengers, flames of fire his servants.” (Psalm 104.4) Barbara Brown Taylor once said that: “To hold a sleeping child in your arms can teach you more about the meaning of life than any 10 books on the subject.” She’s correct. But to catch the deep truth hidden there in plain sight takes slowing down and paying attention: devoted and devout attention. It requires a deliberately unhurried mind and heart intent on seeing and knowing what the Maker of heaven and earth—and of that precious sleeping one—longs to show.

Simply put: It takes an act of slowing life down enough to cultivate wonder, which is one of the reasons God bids his children to practice Sabbath—to take a day off in order to savor life for the sheer and undeserved gift that it is, and then in turn to worship God and to give God thanks for it.

Jonathan Sacks, chief rabbi of London, recalls the time his fellow rabbi, Levi Yitzhak of Berditchev, observed people rushing to and fro in the busy town square. He called out to one fellow: “What are you rushing for?” The reply: “I’m running to make a living.” Yitzhak’s arresting response: “What makes you so sure that your livelihood is in front of you so that you have to rush to catch it up? What if it’s behind you? Maybe you should stop and let it catch up with you.”

Commenting on Yitzhak’s advice, Sacks advises: “At weekly Sabbath intervals we need to stop, pause, and breathe deeply. Jews used to say that food tastes better on the Sabbath. I think they meant, simply, that pleasures taste better when you have time to let them linger on the tongue.”

Practicing joy and wonder, he adds, needs tranquility. To paraphrase Rabbi Levi Yitzhak: Joy and wonder are just behind us, waiting for us to rest so that they can catch up. And catch us up in them.

Theological Reflection

“All earthly delights are springs, but God is the ocean.”

Jonathan Edwards