A worship service from the 2021 online Calvin Symposium on Worship.

Participants:

Organ Prelude

Dr. Joyce Finch Johnson, Professor Emerita of Music and College Organist

Spelman College, Atlanta, GA

Hymn and Choral Selections

Atlanta Martin Luther King, Jr. Ensemble

Dr. James Abbington, conductor

Associate Professor of Church Music and Worship, Candler School of Theology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA / Director of Music Ministries and Church Organist, Friendship Baptist Church, Atlanta, GA

Mr. Timothy Miller, Assistant Professor of Voice and Music

Morehouse College, Atlanta, GA

(soloist for Run Li’l Chillun)

Dr. Lisa M. Weaver, Liturgist and Preacher

Assistant Professor of Worship, Columbia Theological Seminary, Decatur, GA

Dr. Uzee Brown, Jr., Introduction of "We Shall Overcome"

Chair of the Division of Creative and Performing Arts

Morehouse College, Atlanta, GA

Mr. Will Buthod, organist

Minister of Music, Holy Trinity Parish, Decatur, GA

Ms. Ella Lewis, pianist

Organist/Pianist, Sandy Springs Christian Church, Sandy Springs, GA

Organ Postlude

Dr. A. Nathaniel Gumbs, Director of Chapel Music

Yale University, New Haven, CT

Recording Engineer

Kennard Garrett for Westview Drive, LLC

Video Editor and Producer

Rev. Sam White

Director of Admissions

Columbia Theological Seminary, Decatur, GA

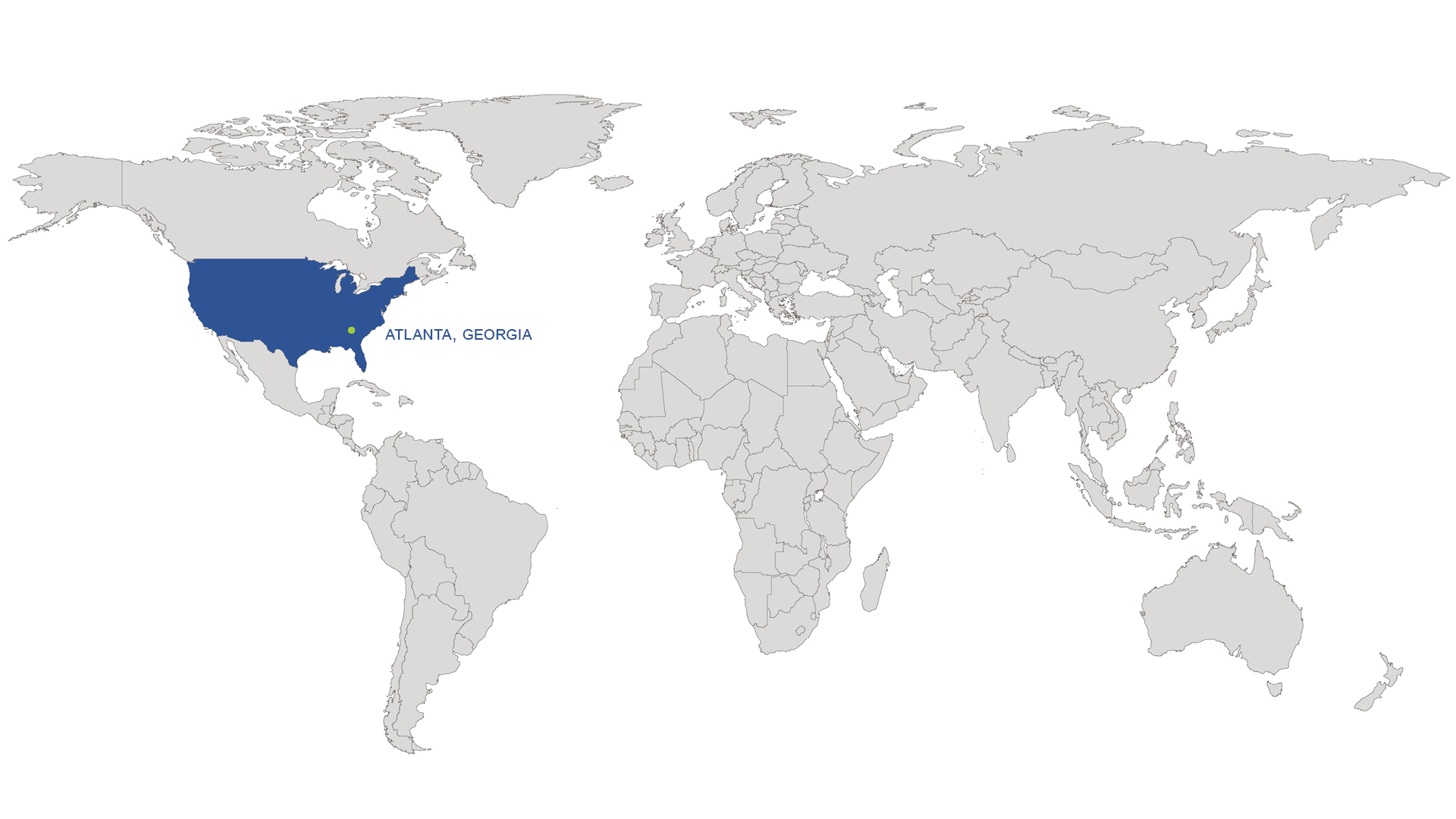

Recording Locations

Columbia Theological Seminary, 701 S. Columbia Drive, Decatur, GA

Friendship Baptist Church, 80 Walnut Street, Atlanta, GA

Second Presbyterian Church, 4055 Poplar Avenue, Memphis, TN

Spelman College Chapel, 440 Westview Drive S.W., Atlanta GA

Copyrights:

"Litanies" Opus 79

Music: Jehan Alain © Alphonse Leduc

Used by permission.

"Lift Every Voice and Sing"

Text: James Weldon Johnson, 1900

Music: J. Rosamond Johnson, 1905

"Run Li’l Chillun"

Text and music: African American Spiritual, Hall Johnson

"We Shall Overcome"

Text and Music: African American Spiritual; arr. Uzee Brown, Jr.

Used by permission.

Improvisation on "We Shall Overcome"

Music: Carl Haywood © GIA Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved. OneLicense.net A-703303.

"Sermon Transcript"

The scripture has been read; I would just like to raise two verses for us to anchor our time together.

Verse 12: “For our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places.”

Verse 18: “Pray in the Spirit at all times in every prayer and supplication. To that end keep alert and always persevere in supplication for all the saints.”

In the time that is ours, I want us to consider this text with this title: “Run, Fight, Vote, and Pray—Because ‘Someday’ Is Coming.” Let us pray.

Good and gracious God of love, justice, and mercy, we are grateful for your Word and grateful that you speak. And so now, God, it is yours to speak and ours to listen. Let every thought that your servant speaks be yours. When your servant speaks let the people hear your voice. May your Word compel and challenge us to greater works of love and justice. And when we are done with this service and this day, may we be resolved and changed in such a way that you get even greater glory and delight out of our lives. This is our confident prayer in Jesus’ name. Amen.

Run, fight, vote, and pray—because “someday” is coming.

In 2016, at the beginning of this administration, many commentators and pundits remarked that it was the ugliest presidential campaign in American history. Scandals about emails and racism, misogyny, tax evasion, unethical business practices; accusations of untruth on both sides—it was ugly, and it was awful.

And now, at the end of this administration, it’s coronavirus and lies. I don’t work for the media; I am not employed by them. So I don’t have to use euphemisms like “having an adversarial relationship with the truth” or “disproven facts” (which is an oxymoron).

In 2020, at the end of this administration, it is coronavirus and a lockdown, lies about an election lost by millions of votes, children in cages separated from parents that cannot be located, emoluments clauses ignored and eroded, stolen Supreme Court Justice seats and the continued assault on the infrastructure of democracy while sheepish sycophants whose bank accounts grow cannot figure out how to congratulate their next boss because they fear their current boss more than God. And on day 2,429, Flint, Michigan, still has no clean water. It’s 2020.

From a theological standpoint, most if not all of this is ungodly. And it should be noted that there is one huge thing that these last four years have reminded some of us of some things others of us have already known: that in America, racism is still a problem; in America, misogyny is still a problem; in America, black and brown women and men are still not safe; in America, Native Americans and Latinx and Asian American people and queer people are still marginalized; Black lives still don’t matter as much as white ones, females as much as males. And so people don’t realize how difficult shallow calls for unity are when you know that people do not fundamentally value who you are as a whole human being, see you as equal, and believe that unity is having you in the room but not in the discussion or the decision. It’s 2020.

And this non-equal valuing of human life is not a political issue. It is not an ideological issue. It is not a philosophical issue. It is a theological one. It is a theological issue that has become perverted in the psychological landscape and roots of many in America. Now, it is informed by many things—too many for this sermon to address. And this sermon is not about theological anthropology; it’s not about politics or presidential campaigns. It is about Someday.

In her article entitled “Ephesians” in True to Our Native Land: An African American New Testament Commentary, Dr. Mitzi Smith writes that “Ephesians reads like a legal document detailing a corporate merger of two major bodies—one foreign (Gentiles) and one domestic (‘the circumcision’)”—Jews. She writes that this merger results in a united church as one body with Christ as its head.

But as we know, sometimes a teacher has to the students to remind them of truths they should already know and exhort them again and again and again to live in these principles.

The writer is presumed to be someone from the Pauline school, not Paul himself. The writing styles are different, so it raises that question. So the writer is someone we will conveniently call “Paul.” In the text there is no particular error or heresy addressed; there is no particular crisis. It is likely written to a mixed audience, and it is written to expand the horizons of the readers so that they may better understand the dimensions of God’s eternal purpose and grace and so that they may come to appreciate the high goals that God has for the church. So it is about expectations of thinking and behavior that the people of God should demonstrate. That is the purpose of this letter.

So in the introduction there is a salutation, there is a blessing, and “Paul” also gives a report and a thanksgiving about the Ephesians’ love toward all the saints. And even with this laudatory comment about who the Ephesian church is, even though there are reports about their love for all the saints, there are still virtues in the Ephesian church in which its members can still grow. There are still places, there are still some growing edges, some places where there are possible opportunities for slippage in which this church can fall. There are some places, some areas—as we say in the Black church, there are some areas where the Ephesian church is prone to backslide. There are some virtues that they need to be reminded of and remember, so the writer writes this letter. And in the body, he reminds them that they’re saved by grace; it is nothing that they have done. They can’t earn it; they are saved by grace. They are no longer strangers and aliens (to) God, but they are members of the household of faith.

The writer identifies himself as “a prisoner for Christ for the Gentiles,” and he exhorts them to live according to their calling. And then he goes on to explain these household codes, these rules that were set forth for governing relationships between husbands and wives, parents and children, and slaver and enslaved. Dr. Smith writes that the household codes in Ephesians reflect “an idealized notion of the hierarchical structure of the Roman household and with early Christianity as a household movement. . . . They prescribe an ideal about how the members of the Christian household ought to conduct their lives in relation to one another.”

[Starting at v. 10] is where we find our text for today, and I must confess that this is the first time this text has troubled me. I have always read this text in a particular way, and this was before seminary, I read this text in a particular manner, and even after seminary. But this time I read the text and I found it troubling, because as I looked at the text and where this pericope is in relation to the rest of the text, it occurred to me, why—after these exhortations about how to live, and how to be in relationship, and that they are one in God, and that they are exhorted for their love of the saints, and they’ve seemed to have mastered some virtues and have a little growing edge on the other—why, after all of this, with no clear heresy, no clear error, no crisis described, why now would the writer put in this militaristic exhortation to gear up like they’re going to war? Interesting that this text . . . follows the text on the enslaved and the enslavers—a problematic text; I will leave that to the New Testament scholars.

But we find this text about putting on armor and being ready for warfare. It’s odd, and I’m still scratching my head about it. But my mind goes back to Dr. Smith’s explanation about households. She writes that they reflect “an idealized notion of a hierarchical structure of the Roman household with early Christianity as a household movement.” There are a couple of problematics in this text, an “idealized notion of the hierarchical structure.” My question is: ideal according to whom? Because depending on who defines ideal, it is less than ideal for somebody else. So there’s a problematic even in this idealized notion. Already I’m beginning to be suspicious about these household codes. But again, I’m going to leave that to the New Testament scholars.

I’m wrestling [with] why is this war language here? Why is this fight language here? Why do the saints have to gear up after they’ve been exhorted for their love? And she also mentions this theological justification for ideal conduct. Whenever theological justification is used, that usually raises my dander; it usually makes me uncomfortable. Because as an African-American woman in this country, I know the theological justifications that have been used to oppress and enslave and brutalize and torture people of color—Black people, Asian people, Latinx people, queer people—the Bible is used as a tool. It makes me nervous. Why do the saints have to go to war?

What I hear in the text is a shift, and perhaps—and this is all my sanctified imagination—what I hear in the text is perhaps this writer trying to reconcile empire and the gospel. What I hear in the text is a writer trying to blend Rome and Christianity in a way that maintains the status quo. What I hear in the text is a writer who knows that when you get two people from opposite ends of the spectrum, from two different cultural backgrounds, from two different ethnic backgrounds, that the merger is not always going to be smooth and easy. What I hear in the text is a writer who recognizes that the human impulse and the human instinct is sometimes to be selfish, is sometimes to be greedy, is sometimes to want what they want, when they want it, how they want it, that the human impulse is to be entitled. What I hear in the text is a writer who recognizes he’s got two groups of people who do not necessarily see eye to eye. I’m not talking about the states; I’m talking about the Bible, empire, and the church.

And it makes me think, it makes me ask: Is war really required for us to be one? Does unity have to come as the result of a fight? It is not mine to answer, and it is far beyond the scope of this sermon, but these are question that this writer is trying to reconcile.

And here we have this exhortation, and he is clear, or explicit, to identify for the church at Ephesus the struggle. He wants to be clear about who the opponents are, what is the object of the struggle. He writes in verse 12: “Our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against spiritual forces in heavenly places.”

I do not think the writer is writing to say that people who are before us—colleagues, politicians, friends, family, church members, fill in your own blank—I don’t think he’s writing to suggest that we don’t have real, flesh-and-blood enemies, but rather that there is something that is at work beyond what and whom we see in front of us. It is not just blood and flesh against whom we wrestle. He wants the church in Ephesus and us to understand that while we have work—I’m going to use all Black church language—while we have work in the earth realm, we also need to understand that we’ve got work in the spirit realm as well. We can’t [just] pray and ask God to fix things; we also have to be engaged in the struggle, in the fight, not only in the earth realm, but in the spirit realm as well. It is not against enemies of flesh and blood, but against rulers, against authorities, against cosmic powers in this present darkness, against spiritual wickedness in high places—that’s old King James language, forgive me—against spiritual forces of evil in heavenly places.

We have all heard these parenthetical descriptions—I have heard them—as different descriptions for the same entity, but I’m wondering now if this writer is not trying to describe four different things. Again, it’s beyond the scope of this sermon, but he is writing to let us know, minimally, that we struggle in the earth realm and the spirit realm.

And, he says, here’s what you need to get dressed: It’s a battle. You’ve got a belt for your waist, the belt of truth. You’ve got a breastplate of righteousness to protect your chest, your heart. What is interesting is that the writer does not have an object for your feet, but writes, “whatever wil make you ready to proclaim the gospel of peace.” And I think there’s something to that, right? Because you have to gird your loins, as the old King James language would say in the old church—like you’ve got something for your waist; you’ve got something for your heart; but recognizing that the gospel is something to be spread, and justice is a fight that is happening everywhere—we’re fighting for justice in all corners of the globe—he says, “whatever makes you ready to proclaim the gospel.”

What I need on my feet in Atlanta might not be what you need on your feet in Michigan. What you need on your feet in Michigan might not be what you need on your feet in California. What the writer is saying is that we need to be ready to proclaim and switch and pivot wherever we are. Whatever you need, whatever gear you need, just make sure whatever it is, it need to make you ready to proclaim the gospel.

Shielf of faith—a very defined object; helmet of salvation; sword of the Spirit—this armor that we need, because now what’s interesting about this piece about the feet being in the middle of these static objects says that it is a gospel that needs to be carried. It is a gospel that needs to be heard. It is a gospel that needs to be proclaimed, not just where we are but wherever we go and to wherever we are called.

Then the writer says, “And pray in the Spirit at all times, in every prayer and supplication.” OK. And “To that end [of praying in the Spirit at all times,] keep alert and always persevere in supplication for the saints.” I’ve read that too quickly all my life, and it wasn’t until this sermon—“persevere in supplication for all the saints”—why is this verse here in an exhortation about battle? Because in battle, I have to remember, after gearing up for the fight, the writer reminds us to pray because we might be battling, [but] we’re not battling alone. We’ve got to pray that the saints in California are strengthened. We’ve got to pray that the saints in Mississippi are strengthened. We’ve got to pray that the saints in Massachusetts are strengthened. We have got to pray for those who are not with us and persevere, because the fight for justice is wearisome, and we get tired. And when we get tired, when I sit down, there needs to be somebody that’s ready to take my baton and keep it moving until I get my energy replenished and I can stand up and take the baton from somebody behind me who now needs to take their rest. We need to persevere for the saints because the fight for justice continues until everybody is free, until everybody gets access, until everybody is a recipient of justice. And so we pray, persevering always in supplication for all the saints.

Now the ancestors didn’t have any fancy armor that this writer is writing about. And slavers made sure that our ancestors had enough to serve them well but barely take care of ourselves. But we just heard how Johnson’s spiritual “Run, Little Children” tell us where to hide, what to put on, and where to stand. So run on down to the Jordan River; cover your face with the fiery pillar—pillar of cloud by day and fire by night. Plant your feet on the Rock of Ages, ‘cause the devil done loose in the land.”

“Run on down to the Jordan River.” We still have to run. We’ve got to run to the voting booths. We’ve got to run to the office. We’ve got to run in ways that will make government change.We’ve still got to fight for justice and equality for African Americans, for Latinx, for women, for Asian Americans, for Native Americans, for queer people, for children, for people who are differently abled. We still have to vote; our ancestors paid for our vote with their very lives. We’ve got to vote until policies are equitable. We’ve got to vote until change comes. We’ve got to vote until the rulers who are trying to rule in high places are unemployed and replaced with somebody who will rule with justice.

And we’ve got to pray without ceasing, always persevering, because someday, someday, someday is coming.

Run. Fight. Vote. And pray. Because someday is coming.

In the name of the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit, amen.