Listen on Spotify, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music, Pandora, RSS Feed.

Episode transcript:

Host:

Welcome to Public Worship and the Christian Life, a podcast by the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship. In this series of conversations, hosted by Calvin Institute of Christian Worship staff members, we invite you to explore connections between the public worship practices of congregations and the dynamics of Christian life and witness in a variety of cultural contexts, including places of work, education, community development, artistic and media engagement, and more. Our conversation partners represent many areas of expertise and a range of Christian traditions offering insights to challenge us as we discern the shape of faithful worship and witness in our own communities. We pray this podcast will nurture curiosity and provide indispensable countercultural wisdom for our life together in Christ.

In this episode, Satrina Reid and Noel Snyder, program managers at the Calvin Worship Institute, engage Fuller Seminary professor Vince Bantu around his passion of bringing together cultural identity and faith and the timely reminder that Christianity has always been a global religion.

Satrina Reid:

Hello from the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship. My name is Satrina Reid. I'm a program manager with the Institute, and I'm here with my colleague Noel Snyder, who is also a program manager with the Institute. Hi, Noel.

Noel Snyder:

Hi, Satrina.

Satrina Reid:

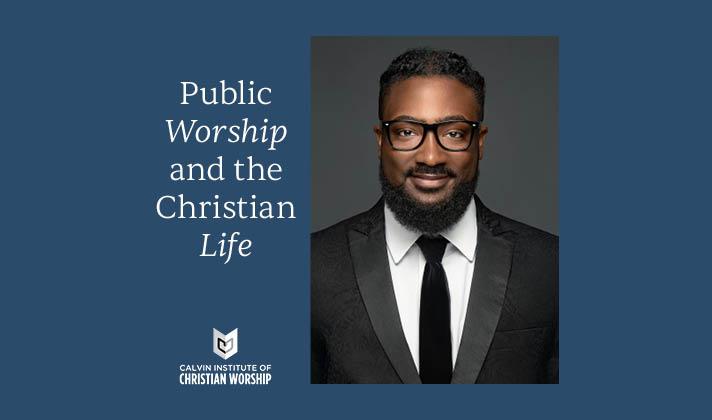

Today we have the distinct pleasure of interviewing Vince Bantu, the author of a brand-new book called A Multitude of All Peoples: Engaging Ancient Christianity's Global Identity. Hi, Vince.

Vince Bantu:

Hey, Satrina.

Satrina Reid:

Before we move any further, I would like to share a little bit about Vince. Vince holds a PhD from the Catholic University of America, and he is an assistant professor of church history and Black church studies at Fuller Theological Seminary. He is also the Ohene, or the director, of the Meachum School of Haymanot in St. Louis, which is a school that provides theological education for urban pastors and leaders. Vince, we're so glad to have you here with us today. Thank you so much for joining us.

Vince Bantu:

Oh, no, it's a blessing. Thanks for having me.

Satrina Reid:

So when I first saw this book--or the book title; I saw the book title before the book came out--I was like, this is what I've been looking for, because if any of us have had experience with theological education or any kind of religious education in the U.S. and abroad, it tends to be kind of one-sided in that you would think that it is truly a white man's religion. And so I'm excited about the second portion of the title, which says "Engaging Ancient Christianity's Global Identity." And then when I flip the book over, it says, "Christianity is not becoming a global religion. It has always been a global religion." And that I think is a very timely title, and it's a timely sentiment for us to discuss today. And so in your writing, tell us the story behind the book and why you decided to write it.

Vince Bantu:

I appreciate it, Satrina. I appreciate you asking that because it really is a book that's connected to my own personal faith journey in Christ, and also my sense of call and ministry because I've always been concerned about issues of cultural identity and faith and how those things intersect. Because ever since I was a kid growing up in the West Side of St. Louis, I always noticed--I grew up in the second hip-hop generation (in the eighties and) nineties. And I always was aware or tuned into the fact that people in my cultural context did not really feel at home in the church. They didn't feel like the place that was really for them or that they could be themselves. And I had a heart for evangelism, so I'd be trying to share the gospel. But at the same time I felt like the church I was growing up in or the churches that I would see in my community were not really accessible for people. And so I had a heart and a passion for reaching people with the gospel in a way that's culturally relevant for them. It's really something that's always been kind of at my heart.

And then, like you mentioned, out of a call to ministry, I ended up going to a Christian college and studying theology, and seminary, and all that kind of stuff. And I appreciated it, but I was also hit with the fact that there wasn't a whole lot of content that reflected me and my people or looked like me or my context. And I didn't see myself or my community in a lot of the things teaching or being taught. And so it was kind of a struggle, and also, especially in courses on theology or church history or anything like that, when we start talking about diversity or non-white or non-European or non-Western voices, we usually wouldn't get to that until we get into the modern world, like into the 20th century. . . . with the perception that Christianity was basically a white man's game until the late 1800s and then the 1900s. And then all of a sudden now black and brown people all over the world are now becoming a part of it.

And so, honestly, . . . even some of the best minds, even some of the greatest agents of issues of culture and identity, like people in missiology, have I think inadvertently contributed to this dynamic of telling the story in that kind of way--to the quote that you mentioned, there are literally books in missiology, in like . . . study Christianity and culture that were worded in that way, saying like, Christianity became a global religion in the great missionary century, or in the modern or in the postmodern world Christianity has become global, or it's finally reached Africa and Asia and all these places. And so that's really what spawned the book.

And when I first got started into this whole field of early non-Western Christianity, which is my main passion, was in my first year in seminary. I took a class where I went to Egypt, and that was the first time I had heard about it. And I was like, wait a minute. I already have an undergrad degree in theology. I didn't hear any of this stuff. This is brand-new. And I was like, man, I gotta get deeper into that. And that's what made me want to go off and do that for my doctorate and write on this. And to show that again, like you said, Christianity has always been global.

Part of my heart as an evangelist who is really trying to reach people, especially in the urban context, and it's a false perception, but it's a very active perception that Christianity is a white man's religion, that it's like antithetical to Black identity or to Native American identity or Asian identity, and so on and so forth. It's a perception that's really all (over the) world. And, you know, the different adjectives will be used: it's an American religion, it's a Western religion, it's a white man's--whatever, but it all has this kind of cultural mapping around it. . . . As much as we point to how much Christianity is--we'll often point out that there are more Christians in Africa and Asia and Latin America than there is in the global North, but people who are struggling with that perception can still point back to, "Yeah, but how did it get there?" A lot of Christianities that are in Africa, Asia, Latin America, they have a very Western flavor to them and they oftentimes entered through Western colonial missions. And so it can still be dismissed for that reason.

And so that's why I feel like it's also helpful to add to the conversation. That's what the book hopes to do, is to add to this global, missiological racial reconciliation, racial justice, decentering Western-eyes Christianity conversation by saying, well, let's look at some other Christian history that a lot of us may not be familiar with that preceded Western colonialism is the vision of it.

Satrina Reid:

That's great. And timely. It's so very timely now.

Noel Snyder:

I'm fascinated with this connection that you've drawn between evangelism or missiology and engaging the ancient history, the ancient global history of Christianity. And I know that this is a relatively new book now that you've published. It's published this year, 2020, so it hasn't been out long, and you probably don't know quite yet how people are going to respond to it, but I'm wondering early responses, or even if you don't have a whole lot of information or feedback from folks, what the response has been, maybe you could comment on how are you hoping that people will engage the book.

Vince Bantu:

That's a great question. It's always fun . . . releasing a book during COVID [laughter]. I haven't had those opportunities to get a lot of feedback and kind of dialogue, right, as much as I would have liked. But, you know, it's also been nice to--kind of adapting to the times I've had a lot of opportunities like this to digitally engage and even do some podcasts with people unpacking different pieces. And honestly, this is the hope for the book. . . . The feedback so far has been, okay, hmm, that's interesting. Like, I didn't know that, like, a lot of just new information and so it's . . . almost like, "Hello. I'd like to introduce you to these missionaries and these theologians and these Christian communities that were in China and India and Ethiopia since antiquity. And again, it's new information for a lot of people. So a lot of people (are) responding, "Wow, I didn't know that. That's very interesting." And so it was a lot of unpacking and things like that.

I think another thing that has been a new thing for a lot of readers is even seeing the things I engage with early in the book, and then it fleshes out throughout, the degrees to which even how Christianity developed in the Western world even, unfortunately, led to a lot of the suppression of Christianity in other parts of the world. I deal a lot with the Council of Chalcedon and kind of the Christological controversies that happened between the Western church and a lot of the churches of Africa and Asia. And again, that's another thing that a lot of people didn't realize and also has a lot of implications for today.

And so that's been something that's new as well, but I'll tell you one thing, a lot of times, in terms of the hope for it, a lot of times when I'm speaking in different places, as an icebreaker, I'll try to introduce the "why" of the book. And I'll ask for people to say by a show of hands, how many of you have ever heard the name Martin Luther, or John Calvin, or Jonathan Edwards, or Thomas Aquinas. You might not know a whole lot about them. You might not be able to quote them, but have you heard their names? And, you know, everybody raises their hands. And a lot of them even know a good deal about these people. But then I'll say, okay, how many of you have heard the name Ephrem the Syrian or Shenouda . . . and nobody's raising their hands. And I'm like, okay, these other names I mentioned are African and Asian theologians that wrote in African and Asian languages. And because of that, most Western historiographers don't even know how to read their language because they didn't write in Greek or Latin in the interior of the Western world. And so they're not as known, and that's the very problem that we're living with.

But that's what the book seeks to address, is to make these African and Asian names as household as the European, Western names are and have been. So that's the hope of the book, to both be like a "Hello, nice to meet you" to early African and Asian Christianity, but then also to reflect on what are the lessons that we can learn? Because that's what I, as an evangelist and as a Christian but (who) also who loves history, for me, they have to go together. History for me is not a dry kind of, "Oh, I just want to talk about this just because it's interesting." But for me, I always share with my students in class, for when we look at history, what is the value of history for believers? For me, the main passage is always Hebrews 13:7, where the writer has just taken the audience of Christians on a historical tour of the saints and of all of the great pillars of the faith saying, "Remember these leaders and think about their way of life and imitate their faith."

And so for me, it's also looking at what are ways we can learn from this and what are ways in which there's still issues with one dominant voice in Christianity that's suppressing and not giving voice to other members of the body of Christ that also are indispensable. You know, as Paul says in 1 Corinthians 12. That's also the hope--is that we can really learn those lessons.

Satrina Reid:

That's so rich. It's so rich. And wondering--I don't know how long it took you to write the book, but since writing, or even in the process of your writing, how has your thinking changed or did your thinking change as you were doing your own research and writing, from the start to now, are there any ways that your thinking has changed?

Vince Bantu:

That's a great question. That's an interesting question. Nobody's asked me that before. . . . I don't even know if it's changed so much as grown or gone deeper, but actually, it was about a five-year journey to get the book from the genesis of it to the publication. I probably wrote the thing in about a year, but, you know, I think during that time, I actually have personally gone deeper in this value of like decolonization, right? Especially at Fuller that's a big language we use, like decentering whiteness, for example, in theological discourse.

And so a specific example is--I got saved when I was seven years old. I came to know Jesus as my Lord and Savior, and I gave my life to Christ when I was like seven years old. And I was in ministry, in middle school, high school. So I'm just saying that I had like over ten years of Christian experience before I came to a Christian college. And so I was coming into Christian college as a little 19-year-old, but I was coming into it like, oh, I'm on furlough now. [laughter] I need to go and learn and all that kind of stuff. I was a strong believer for over ten years before I even heard what an evangelical is, you know what I'm saying? And like evangelical is kind of a suburban, upper-middle class term. You don't see people in low-income communities walking around calling themselves evangelicals. And so I went to a Christian college, and they were like, Oh, you're evangelical. And I'm like, I don't know what that is, you know? And . . . I'm like, I'm a Christian, I'm saved, I'm sanctified, I'm filled with the Holy Ghost, I'm a believer. . . . (But) I guess . . . whatever , if you want to call it that.

Satrina Reid:

I didn't know what an evangelical was either.

Vince Bantu:

And now all I'm saying is that I get introduced to all this theological language that is unfamiliar to me and I'm doing my homework and I'm reading my readings and I'm getting inundated with all these eschatology, hermeneutics, hamartiology, and kenosis, and I'm like, okay, all right. And then I'm reading French and German terms, like this is the Sitz im Leben and zeitgeists and all this. And I'm reading academic writing, and I see all this European language just getting dropped left and right, just put in there, like it makes it fancier, you know , when you put it in a Latin phrase and we're here now pronouncing African terms, right? Like we're here talking about . . . Haymanot, that's something that actually I've really kind of changed and grown into, even during the writing process was like, that's something that I've really seen is that's a way that we can decenter whiteness by not always in academic writing to always just be dropping these European terms, whether they're French, German, Dutch, Greek, Latin, whatever--and that's cool, we can do that, but that means we can also do it with African terms as well, or Asian, or whatever.

One of the things that I point out in the book is that Christianity wasn't even called Christianity in early times. It was called the Jingjiao, which means "the luminous way." So that's something that I do as a person of African descent is really trying to lift up, especially ancient African Christian theological terms like Haymanot, for example, which is an Ethiopian term that means theology, but it's a very holistic term. It means faith, doctrine, way of life, theology, belief system, it means all of that. It's a very holistic kind of concept. And so that's been a term that I use in addition to theology, which is kind a Greek term.

And so that's been one thing that I've really, even in my writing---and it's funny because I've actually gotten some pushback from publishers on it and I've pushed right back, you know, and I would call it out and be like, what's up with that? Like why? Because they would even say things like, Oh, well that's kind of distracting or it's very off-putting, or it's very different, and stuff like that. But I'm like, Okay, but in your very publication, you publish things by white theologians and scholars or scholars of color that is inundated with European terms, that--your average Joe is not going to know what the word perichoresis means, right? And yet Christian publishers will just drop that word in there and expect you to jump on board. I'm saying, okay, . . . I'll put the African term in there, but again, do we really mean it when we say we want to decenter whiteness, and we want to really, again, (bring in) all members of the body of Christ?

This is one way that I have grown, even in the process of writing this book, I've kind of grown. And honestly, even in my own faith journey, I've gotten to a point now where I am more and more referring to the Creator, to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, with the word "Tila." Now "Tila" is actually the ancient Kushite word for--it was actually an ancient Kushite deity that when the Nubians became Christian, a Christian nation--and it talks about that in the book--in the sixth century, when they began to translate the Bible, they took this pre-Christian word "Tila" and they used it to translate "theos" in the Bible or Elohim, or Yahweh in the Bible, they translated as "Tila," right? And so I'm actually--even in my prayer life where I refer to the Creator as "Tila"--it's very empowering to me as a black person on this side of the transatlantic slave trade, to be able to refer to the Creator by using the name in the oldest black civilization known to humanity, which is the Nubians, and use their words. Because again, the word "god," if we look at it etymologically, that comes from Anglo-Saxon/Germanic paganism, right? It's related to the word for Odin--Odin, Woden, guthan, god--so every time we say the word "god," we are using a term that originates in European paganism.

And that's okay, because again, the gospel comes in and embraces all culture and uses and transforms and redirects all culture to glorify the one savior Lord Jesus Christ. But if that's true for European culture with Christmas trees and Christmas wreaths, then that can be true as well for African and Native. So that's been something that I've--it's just been very empowering, and that's a recent kind of change.

Host:

You are listening to Public Worship and the Christian Life: Conversations for the Journey, a podcast produced by the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship. Check out our website at worship.calvin.edu for resources related to this topic and many other aspects of public worship.

Noel Snyder:

I'm wondering--because we're the the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship--of course we are interested in engaging lots of different things with the question oftentimes of how it might connect to worship. And so I'm wondering if you could reflect a little bit on any ways that you think the material in your book would connect to worship practices in congregations in North America or maybe even beyond North America.

Vince Bantu:

That's a great question. I think that worship is such a powerful way to really apply a lot of the same value that hopefully all of us as a global body are starting to have. You know, the Holy Spirit fell at Pentecost and every language was heightened and enhanced. It wasn't everyone speaking Aramaic or Greek; every language was enhanced. So "Tila" even exists eternally in diversity, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, three in one. And so in his own eternal diversity, Tila creates humanity in diversity on purpose and chooses to be glorified. And that's an eternal reality, right? Revelation 7:9. It's not when we get to heaven, we're all going to be the same. We're still going to be different and distinct. And so worship is such a powerful way to really help us feel that, help us feel that diversity in a Sunday service or in other Christian gatherings where through musical and other artistic forms, that is the perfect venue to really live out the reality that the gospel comes into culture and says, "This is mine. This belongs to me. And this is something that I'm going to transform, but also embrace in order to glorify the Lord Jesus Christ."

And there's even aspects of the book that really touch on ways in which some of these early Christians in the non-Western world specifically engaged. Yared is a name that a lot of us don't know. He's somebody I touched on briefly in the book, but there's a deep, rich history where he was a saint from the sixth century in Ethiopia who created the Ethiopian style of the liturgy. So the Ethiopian Orthodox church today has its own form of liturgy with three distinct chants that all have distinct functions and musical hymns and rhythmic patterns. And I mean, I'm not a musician, but his story is very pivotal for the entire Ethiopian people. And it's attributed that he got this new style literally as a direct revelation from God--in the Ethiopian language, the word for God is "Igziabeher," which means the Lord of the land--that the Lord of the land, Igziabeher gave Yared this music, that his biography says, the Spirit gave him sound that did not exist in any human or animal form, that these were heavenly musical forms that's so much a part of the Ethiopian identity.

Another example is Ephrem the Syrian. Ephrem the Syrian is one of those names that so many people don't know. And it's a travesty because he's one of the most prolific early Christian authors in the history of the church in any culture. But he wrote in the Syriac language, which is a dialect of Aramaic. And one of the beautiful things about Ephrem is that he did theology through the form of poetry. . . . This is one of the lessons we need to learn, right? As we as a church and academic institutions today are trying to live into the reality of God's global body, one of the pitfalls we'll fall into often is we will try to recruit people who look different to come and lead. But we want them to lead like us and so kind of assimilate and be like us, right? And so one of the beautiful things about Ephrem, for example, is that he's not only an early church father, but he does not write like most of the early church fathers that we're used to reading like Basil of Caesarea or Athanasius or Augustine. He doesn't write according to a Greco-Roman, Hellenistic frame of mind, but he writes in a very Semitic, Syrian way. And as I mentioned, he writes literally in the genre of poetry. It was a unique style of poetry called " midrase." It wasn't like poetry in the Western context of it being only a purely literary thing; it was literature, but it was also musical. They were set to music and they had certain syllable patterns that rhymed and had all these beautiful Syriac wordplays and alliterations, and they were set to a certain tone in music. And they had a quiet background where the chanter or the orator would have a choir singing in the background. And then there would be--the audience would have an unito or a chorus that they would recite. . . . They were meant to be publicly recited and performed. And this was the methodology that Ephrem used, literally singing theological education. He's the most influential theologian in the history of the Syriac--all of its branches and all of its denominations. He is the single most greatest influential author. And his greatest genre of literature was this musical poetry. It's a great example of the cultural flexibility of the gospel and specifically the power of worship and how worship can just really magnify the beautiful diversity of the body and also the greatness of our Lord.

Satrina Reid:

Wow. This is just so rich. So rich. Thank you so much. I think as we look at engaging ancient Christianity's global identity, we recognize that we tend to like being in sameness and in homogenous places with people who are like us, think like us, who worship like us. So I'm wondering with this book, I'm excited about it, what opportunities or challenges does it presents to some churches and worshiping communities?

Vince Bantu:

That's a great question, Satrina. I think one of the challenges that'll come up is the way in which the book reveals that there were issues in church history, as I mentioned, where there were schisms, and one particular dominant voice in the church felt that it had the monopoly on how to do church and began to impose that upon other believers who had a different perspective and had a different dynamic. I mean, connected with missiology and, for example, Andrew Walls, the classical missiologist, has a great example for how to describe the reality of the cultural diversity of the church. And he describes it like a theater, an audience watching a play in a theater, and the play is the gospel and the audience is the church, and we're all looking at the same play of the gospel as revealed through the Holy Spirit and scripture, but we're looking at it from different perspectives. And so our perspective will change and it will also affect how we engage with, because again, as we know, revelation is a divine work of God, but theology, and worship, and whatever we do is a human work.

Therefore it is by nature culturally specific and therefore by nature also incomplete. And as much as it reflects the glory of God, it also is fallible, our theology. God's word is infallible, but our theology and our works are not infallible. And it's also human and it's particular to historical and cultural context. So it's ridiculous for any of us to think that our worship or our doctrines, or our theological statements, or our style of doing church is the end all, be all, or is the exact mirror reflection of God's perfect and holy Word. Right? But what happens often in church history, as the book reveals, that what happened--to go with Walls's theater analogy--is you have one person in the theater who thinks, well, my seat in this theater is the best and I have the best view and I can see all of this thing. And let's say that person is sitting over on stage left, and they don't even see things that are way over on the right side of the stage, but yet they think because of whatever reason, maybe their seat has better funding, maybe their seat has better cushions than everyone else's, that that makes their perspective--but only God has the backstage pass. Only God has the director's of view of everything, right? But we will think that our seat is better, our perspective is better, and we'll say, I don't even need the perspective of the person that's way over there on the right, when actually that person on the right, they're seeing things in the play that you can't even see, and that your perspective will only be enriched by listening to theirs. And actually you have things to teach them, but they also have a lot of things to teach you as well. And that's something that we have not really learned as a church.

And I think it'll still be a challenge to see that today, to really see ways in which we have meshed together our ethnic and cultural and national values. And we've seen those as being synonymous with our identity in Christ, and especially if you are in the dominant culture--trying to explain dominant cultural values to a person in the dominant culture is like trying to explain water to a fish because it's just the water you swim in. And it's like, no, this isn't my culture. This is just normal. This is values. These are universal. And sometimes they are universal, but a lot of times they're actually not. And they're actually your cultural values, right?

You know, punctuality or time orientation versus event orientation. There's nothing like universal about that. You could be time oriented or event oriented. You could have a service that goes three hours long, and we're just going to go where the Spirit leads us, or you can have a service as an hour and seven minutes and your sermon had better not be over twenty-two minutes. When we start to take our cultural values and say, these are synonymous with God's values, that's when we get into trouble. And it's often hard to do that when the world around you is kind of built for your cultural values, it's hard to see the specific cultural biases that don't need to be universal for everybody. And I think that's one of the challenges, but it's also an opportunity . . . to look at and really take an honest assessment of, well, what are my cultural values and how have I maybe kind of lorded those over all and conflated them with biblical universal values and how can I start to distinguish those things--not even necessarily separate them, because again, all of us are made in culture and God can embrace all of our cultures, but how can I not lord those over other people? And how can I impose those things over other people? And also, how can we--just as we are going back and elevating again the parts of the body that the world has seen as weaker which are actually indispensable, how can we give greater honor to the parts of the body that have lacked it in historiography and in the same way, the opportunity is how can we then therefore give greater honor to the parts of the body that are even lacking it right now, even in the world that we're living.

Satrina Reid:

I wish we could just keep going. I wish we could keep going. Thank you so much. God bless you and your work; God bless this book, A Multitude of All Peoples: Engaging Ancient Christianity's Global Identity. What a gift; what a gift. We are so glad to have had you today. And I don't know about, Noel, but I think my life has been enriched just in these last few minutes of hearing about how God inspired you and moved you to write this book. . . I think it's just very timely. So thank you, and we look forward to talking to you again sometime.

Vince Bantu:

Thank you. I do as well.

Noel Snyder:

Thank you so much.

Host:

Thanks for listening. We invite you to visit our website at worship.calvin.edu to learn more about the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship, an interdisciplinary study and ministry center dedicated to the scholarly study of the theology, history, and practice of Christian worship and the renewal of worship in worshiping communities across North America and beyond.