A worship service from the 2021 online Calvin Symposium on Worship.

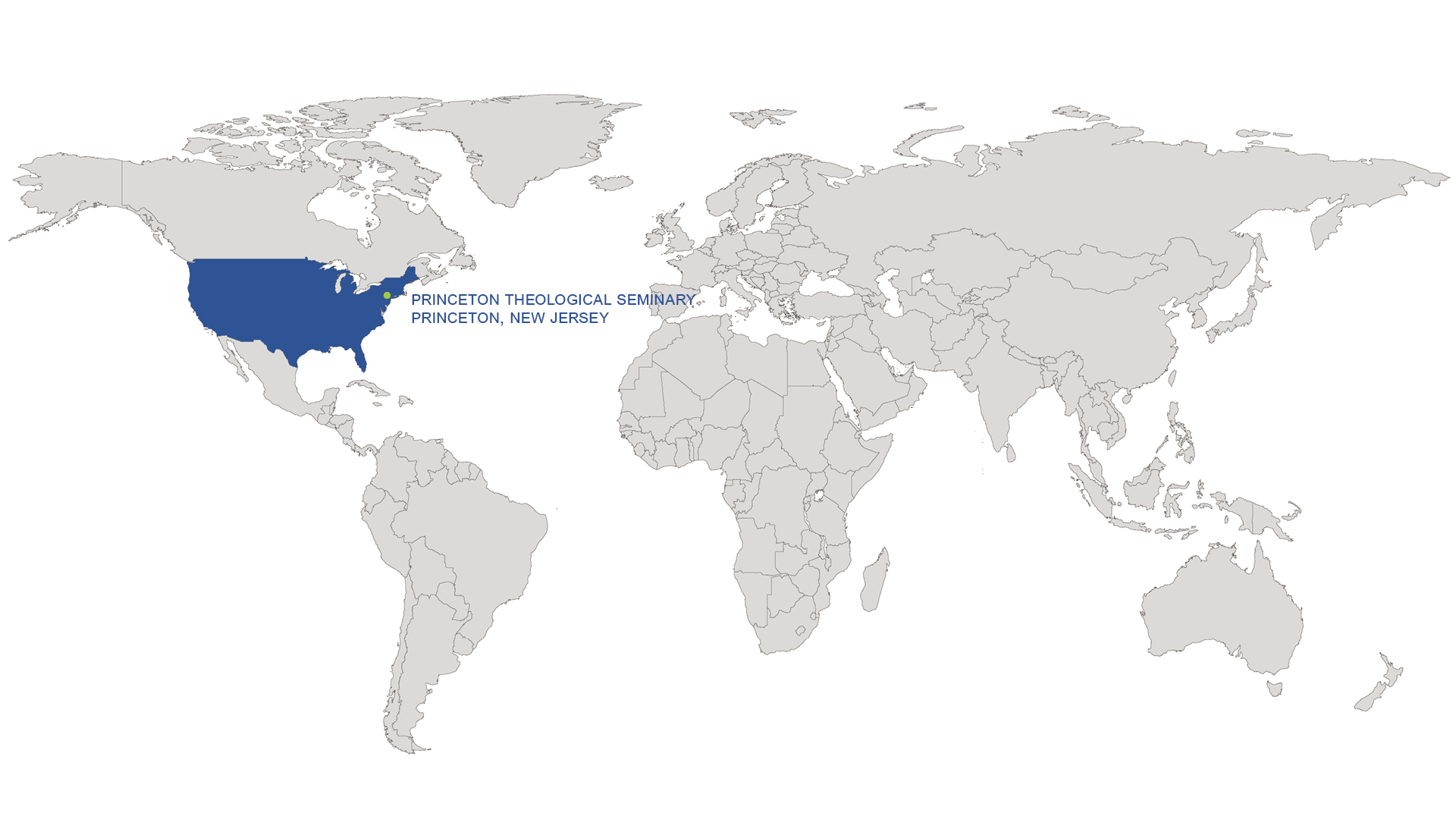

Institution Name: Princeton Theological Seminary

Participants:

Introduction of Worship: Janice Smith Ammon, Melissa Haupt, and Martin Tel

Opening Sentences: Kenneth Oduor Ofula

"Clap Your Hands" soloist: Allie Senyard

Call to Confession: Sarah Chae

"And Can It Be" accompanist: Michael Ryan

Romans 8:26-30 reading: Noah Buchholz

Sermon: Eric Barreto

Wordless Is the Prayer"

Melissa Haupt, soloist

Michael Gittens, organ and piano

Mckenzie Kramer, cello

Bethany Cok, violin

Hyun Kyoung Kim, flute

Eric Rasmussen, guitar

"And Jesus Said" soloist: Rachel Boden

Princeton Seminary Chapel Choir

Soprano

Olivia Flint

Melissa Haupt

Katrina Heath

Rachel Johnson

Maddie Lannon

Austin Shelley

Emilyanne Shelley

Emily Sutphin

Alto

Rachel Boden

Margaret Brungard

Sarah Chae

Megan DeWald

Kelsey Lambright

Alex Miller-Knaack

Tanya Regli

Allie Senyard

Ellen White

Chelsea Williams

Tara Woodward

Tenor

Luke Bultena

Otis Byrd, Jr.

Noah Gourlie

Andy Jones

Jeremy Kim

Brian Regli

Bass

Henry Burt

Ryon Herin

David King

James Klotz

Riley Lannon

Peter Manning

Char Mansfield

Wesley Rowell

Brandon Smee

Location: Princeton, New Jersey, USA

Order of Worship and Copyrights:

Introduction of Worship: “More than Words”

Handclapping Prelude

Opening Sentences: Psalm 47:1, 7-8

Song: "Clap Your Hands"

Text: Greg Scheer © 2009 Greg Scheer

Music: Yoruba folk song; adapt. Godwin Sadoh © Wayne Leupold Editions, Inc.; harm. Greg Scheer © 2009 Greg Scheer

All rights reserved. OneLicense.net A-703303.

Used by permission. CCLI #400063.

Call to Silent Praise: Psalm 65:1-2

Quiet

Call to Confession

Choral Response: "And Can It Be"

Text: Charles Wesley

Music: Dan Forrest © 2014 Beckenhorst Press, Inc.

All rights reserved. OneLicense.net A-703303.

Prayer

Scripture: Romans 8:26-30

Sermon: "More than Words"

Choral Response: "Wordless Is the Prayer"

Text: Carl Daw © 2016 Hope Publishing Company

Music: Sally Ann Morris © 2016 GIA Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved. OneLicense.net A-703303.

Prayer

Song: "I Love the Lord Who Heard My Cry"

Text: Isaac Watts

Music: African American spiritual; harm. Richard Smallwood © 1975, 2003 Century Oak Publishing Group/Richwood Music, admin. Conexion Media Group, Inc.; arr. Dave Maddux

Used by permission. CCLI #400063.

Blessing

Choral Response: "And Jesus Said"

Text: Shirley Erena Murray © 1999 Hope Publishing Company

Music: Ben Brody © 2017 GIA Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved. OneLicense.net A-703303.

"Sermon Transcript"

Let me fill you in a not so little secret: preachers love words. We believe that our words, frail as they may be, are words that God has called us to voice. Words, we believe, can bear within them the good news of Jesus, the gospel that God has drawn near to each and everyone of us. Professors too love words. We relish the many ways words can mean. We relish that moment when the words of a teacher become the insights of students who speaks in her own distinctive voice. We see the power of words to help us all see the world a little bit differently, to learn from the courage and errors of the past alike.

We love words. But the truth is that our words—no matter how crafted—our speech—no matter how precise—our proclamation—no matter how truthful, our words can harm. Our words can divide. Our words can kill.

As James notes, the same lips that can voice love of neighbor can also strike him down.

Paul is a fellow aficionado of words. In Romans, we can sense the poetry and passion of his theology. But Paul here knows well the limits of our words, the places our words cannot take us, the powerlessness of our words facing a broken, hurting world.

I don’t know about you, but I have been struck by the inadequacy of our words in a world ravaged by death and political incompetence and our lack of care for our neighbors. None of our words can bring back the hundreds of thousands of people who have died of coronavirus. None of our words can heal the 3000 Puerto Ricans swept away in the waves of Hurricane Maria. None of our words can stem the flow of tears of 345 children torn from their parent’s arms at the border and not yet reunited.

My friends, this preacher, this scholar, this lover of words and their power, I shrink before the realities of a world marked not by God’s justice and grace but by the distorting force of empire and colonialism, racism and misogyny.

If I’m honest, I just do not know what to say right now. Words seem insufficient. Words seem inert. Words are not simply up to the task. In a moment of crisis and uncertainty, our words fall short, whether we are seeking to explain the whys of life or even when we are voicing a prayer.

So we preachers, we teachers, we theologians are left with no choice but to confess something that might strike our hearts with fear, something that might make us wonder where else to turn. Words are not up to the task so often. Faced with a shattered world, we come up short.

But what if that is good news? What if the inadequacy of our words is a kind of freedom we desperately need?

If we incline our ears just so, if we look around at the just the right angle, we might just hear, we might just see, we might just feel something else, or better, someone else under the rumble of our often heedless, often inadequate, even sometimes harmful words.

Under all those frail words, there is a prayer.

Choral Response “Wordless Is the Prayer” arr. Sally Ann Morris

Under all those frail words, there is a prayer.

This is Alexander Oratory on the Princeton Theological Seminary campus. So many faculty meetings have happened here. So many classes hosted. So many students gathered here just a few steps away from their dorm rooms. This room is filled with generations of words. I’m sure life-giving words have been voiced here. Students helping students. Teachers shaping young ministers. Faculty meetings considering the future of theological education.

But we know that the teaching and theological assertions of our predecessors in this space claimed a theological and political outlook that could not imagine how white communities and black communities could co-exist. That the return of black folk to the African continent was the only way forward. In this room, words taught. Words also harmed.

In the verses leading up to our passage, Paul reflects on suffering, concluding that the suffering we now experience, the afflictions we now feel are echoed across all creation. When we suffer, creation moans. When we hurt, creation groans. Our grief is not a silent cry before a God who has shut God’s ears. Our grief is not a hidden loss from whom God turns. Instead, our grief is a wordless echo that rings throughout all of creation. Our losses are evoked with sighs deeper, clearer, that much more tangible that whatever words we might utter.

Suffering, Paul says, is a cosmic reality interwoven with innumerable personal realities. This grief I feel, this suffering I experience redounds in the breadth of God’s creation. Also, Paul teaches us, suffering is a communal exercise in this way as our cries echo throughout creation. Yes, suffering is communal and cosmic but so too is the redemption God is already enacting and will bring to completion one day. The redemption Paul narrates bursts through the confines of any one individual life or even human life as that redemption brings all of creation into alignment with God’s creative, graceful, just purposes.

And so we wait for now. We await the redemption of our bodies in hope, in expectation, but also in prophetic demand. That is, the kind of waiting Paul narrates here is neither passive nor patient. The kind of waiting Paul describes is demanding in its prophetic stance. The world ought not be this way. The world ought not be pockmarked by death and violence. The good creation ought not be burdened by loss and grief. God’s creation ought not be mired in sin and injustice. Even the rocks echo our prophetic supplications. Even the nonhuman animals join the chorus of grief. The very air trembles as we together await the fulfillment of creation’s purposes.

It is in light of that hope that Paul now declares the intercessory power of the Spirit. The intercessory power of the Spirit is not an anesthetic to dull our pain nor a simple promissory note that says things will be better one day nor a mere fantasy into which we can escape, if but for a moment, the cruelties and indignities of world bent around sin and injustice. No, the intercessory power of the Spirit is prophetic. That intercessory power of the Spirit is characterized by a “… hope that guides through gloom and doubt” as we will sing shortly. That hope is hard-won in the trenches of life. That hope won’t be satisfied to have pain softened or dismissed. That hope screams that pain into the depths of creation. That hope calls out to God who has promised to set the world free. That hope calls out to a God whose grace is abundant.

And here’s the truth, friends. All the ways we seek to understand, to explain, to detail these realities fall short. Even Paul here falls short because words are not up to the task of describing the pain of suffering creation echoes and the hope of deliverance God has promised.

Under all those frail words, there is a prayer rooted in hope.

Choral Response “Wordless Is the Prayer”

Under all those frail words, there is a prayer rooted in hope.

Even all these books in this library, all the lives they represent, all the toil their covers enfold, all the true insight and inspiration they contain, even with all these books, our words are frail. The sighs of the Spirit far exceed the power of our words. We know, don’t we, that words can do so much harm. And here some of Paul’s own words have been turn from hope to loss, from an amplification of grace to the multiplication of grief. “We know that all things work together for good for those who love God, who are called according to God’s purpose,” Paul writes. For some, just hearing those words, takes us back to difficult moment. Moments when our faith was frayed, when our grief felt overwhelming, when sadness weighed on us so that it felt like it would never end. Just hearing those words, takes some of us back to those moments and so many supposedly well-intentioned efforts to help stitch together our faith again, to dissipate grief, to lift the weight of sadness.

So often, we try to leverage this verse to explain away grief and loss, to apply this verse like a miraculous salve on a wound still stinging, still vulnerable, still a long way from healing.

This happened for a reason. This was God’s plan. God needed another angel. Time heals all wounds. Chin up. Get over it. If you prayed hard enough, you would be healed.

Every word cuts deeper and deeper. Every syllable spiraling us further into grief. Every letter having the opposite effect intended by the speaker so desperate to make sense of the terrible, the unexplainable. In Everything Happens for a Reason … and Other Lies I’ve Loved Kate Bowler has written about her experience after being diagnosed with cancer. She writes, “But most everyone I meet is dying to make me certain. They want me to know, without a doubt, that there is a hidden logic to this seeming chaos.” Perhaps our instinct is to fill air full of grief with words because the silence is just too terrifying. Apparently, it is harder for so many of us to be silent before terror, quiet before grief. What if silence, accompaniment, presence is a more powerful ministry in these moments than all the words we can muster?

Under all those frail words, there is a prayer rooted in hope and the strength to move.

Choral Response “Wordless Is the Prayer”

Under all those frail words, there is a prayer rooted in hope and the strength to move.

Paul writes, “We know that all things work together for good for those who love God, who are called according to God’s purpose.”

We know.

But do we? Do I know? Do you? What does it mean to know that “all things work together for good for those who love God?” To too many in a world where we mistake privilege for blessing, “all things work together for good for those who love God” means don’t worry; it will all be alright. This will pass. Maybe things aren’t working out for you because you don’t really love God, you don’t really try hard enough, you aren’t actually beloved of God.

We know. “We know that all things work together for good for those who love God, who are called according to God’s purpose.”

We know? I can’t help but wonder if Paul was a bit too confident in what we know. Did Paul overstate this insight, this knowledge?

But what if we misunderstand Paul’s “we know” because we read this one verse apart from a larger context and apart from a larger hope?

What if the “we know” here has less to do with the words we speak, the ideas we share, those hopes we can voice, those wise explanations we have conjured? What if the “we know” is not about all that but is instead about an embodied, everyday trust in God’s promise? It’s less about what we say and more about how we move through the world among the dying and the dead, how we move through the world in light of God’s promise. When Paul confesses that “we know that all things work together for God for those who love God,” his confession is closer to a sigh than a “wordy” understanding.

There is another piece of context that is vital here. Here Paul declares what we know. But just a few verses earlier, Paul reminded us what we do not know. “Likewise the Spirit helps us in our weakness; for we do not know how to pray as we ought, but that very Spirit intercedes with sighs too deep for words.”

What if the space between “We don’t know” and “we know” is where Paul is calling us to imagine ourselves living and moving and having our being? What if God’s promise fills the space between what we don’t know and what we know? What if God’s promise is that space between the Spirit’s intercession and our confidence in God’s grace? And what if when we seek to fill that ineffable space with every word we can muster, every understanding we think we have built, every bit of clarity we have constructed, we miss the still silence of God filling out every hope we have, hearing every bit of suffering we have born, healing every wound, drying every tear.

This is the Farminary, a former sod farm which is now part of the Seminary campus. Christmas trees were grown here too. This land upon which we stand has seen and heard so much suffering. This is the land of the Lenni-Lenape peoples, taken and seized. This is a land that has heard the sounds of colonialism. Just down the road is the Princeton Battlefield where American and British soldiers alike fought and died. This is a land that has cradled the dying. The soil of the farm had lost its richness having been used to grow sod to adorn front yards more concerned with a look than the flourishing of land and plant and human alike. This is a land that has known neglect. And now this land hosts conversations about ultimate matters. This land is being brought back to vibrant life with every turn of the spade. This land hosts the pain of students and faculty alike, our wondering about the future, our hope for a sustainable life on God’s good creation. The land has a memory, and it has a song, if we can but incline our ears to hear it. The land is singing and mourning alike. Earlier in Romans Paul writes, “We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now.” Perhaps that groan, like the Spirit’s sighs, are wordless.

Under all those frail words, there is a prayer rooted in hope and the strength to move and the realization that there is a kind of joy that is wordless.

Choral Response “Wordless Is the Prayer”

Under all those frail words, there is a prayer rooted in hope and the strength to move and the realization that there is a kind of joy that is wordless.

When my words run short, I often find myself frustrated, even disappointed in myself. When I can’t find that right word when I’m writing or teaching or preaching, I tend to chalk it up to being tired or stressed. When I can’t find the right words to ease the pain of someone I love, I wonder why I have fallen short. When I can’t find the right words, I wonder if I’m simply just not good enough.

But maybe I’ve gotten this all wrong.

When my words run out, when words fall short, when words are simply not enough, what if God is leading us to … joy? To the joy we feel when we know God’s sighs are far more than any words I could ever utter. To the joy we experience when someone abides in our hurts. To the joy we know when God has drawn near. To that joy that washes over us like the waters of baptism, the moving of the Spirit, the dawning of resurrection life.

Let’s be clear, that kind of joy is hard-won and costly and precious and often quite fragile. And that fragile, precious joy fuels a transformative hope.

A few years ago, I saw a something that lingers with me still. In the wake of yet another of a long litany of police shootings of black folk, students gathered on these steps. And they prayed. And they called out. And they demanded justice from God and from anyone who would listen.

But when I first saw those students, I was far enough away that I couldn’t hear their voices or their prayers just yet. I couldn’t hear them. But I could hear a wordless prayer, discern the sighs of the Spirit, and see an embodied hope that has fueled me ever since. In these students on these steps, I felt God’s call upon their lives and mine.

It turns out that when God works together good for those who love God, that working together good for those who love God is not linear. That working together good for those who love God is not akin to a warranty on a product we just bought, something we might cash in when things go wrong. That working together good for those who love God is a promise, an assurance that God is faithful.

In the end, our words fall short before a promise: the assurance that God is faithful. And that assurance cannot be explained with mere words. It is heard in the sighs of suffering, felt in the tears of the mourning, embodied in the cries of the prophet and the protestor.

That is, under those frail words, there is a prayer rooted in hope and the strength to move and the realization that there is a kind of freedom that is wordless. Under those words, under that prayer, under that hope, under that strength, under that joy, there is a promise and the one who promises. Before the one who promises to draw near to us to the very end, I run out of words of praise and grief alike. Before the one who promises abundant life, I’m left speechless. Before the one who promises to set the world right, I’m filled with a grace I can barely describe.