Preachers often describe the Bible as God’s Story, a grand narrative that interprets the real world. They remind us that everyone, intentionally or not, lives out of a story that makes sense of human history. They ask us to choose to see our lives within the biblical drama of redemption.

But here’s the problem. What we sing, say, hear or do in worship doesn’t always reveal how God’s Story makes sense of things that break our hearts and hammer away in our minds. Whether because of poor choices or circumstances we can’t control, we stagger under sin, sorrow, poverty and racism. Yet we often sidestep these issues in worship.

Visual artists create images that make us question the labels we use to decide what fits in worship or who God loves. “Art doesn’t ask of you any affiliation before it claims your heart,” Chandler Stokes said at the 2014 “Who Is My Neighbor?” conference and art exhibit in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He recalled the Luke 10 story of the lawyer who wanted to justify his hold on eternal life and who asked Jesus, “Who is my neighbor?” Jesus told him about the Good Samaritan.

“Our hope for this conference is for people to welcome art into their hearts and become transformed,” said Stokes, pastor of Westminster Presbyterian Church in Grand Rapids. Artists Steve Prince, Linda Witte Henke and Sergio Gomez helped conference participants talk about what keeps Christians from exploring God’s call to love our neighbors as ourselves.

From brokenness to beauty

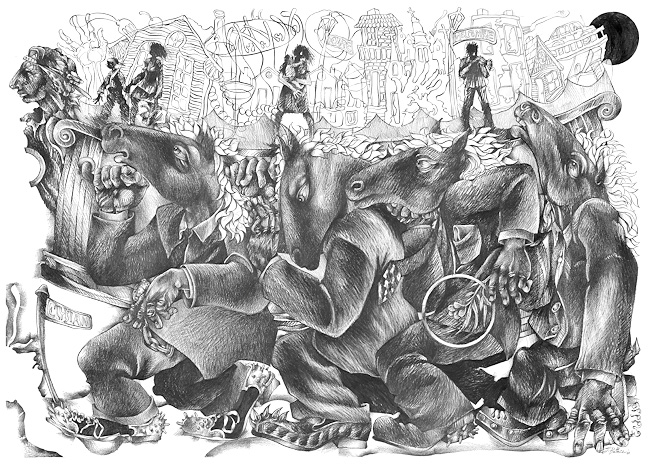

Steve Prince is an artist, educator and self-described “art evangelist” who grew up Catholic in New Orleans, Louisiana. “Where is the outcry from Christians about all that’s going wrong? To get to the beauty you have to go through the brokenness,” he said at the conference.

Prince describes each of his works as “a story, a truth that must be told.” His charcoal drawings and linoleum block prints are dense with biblical, literary, historical and cultural symbolism. His Katrina Suite, a series about Hurricane Katrina, draws on New Orleans’ funeral traditions. As people walk to the cemetery, a band plays dirges—sad songs. After the committal, the band switches to upbeat music and the people dance to celebrate the deceased being cut loose from earthly pain.

In “Katrina’s Dirge,” four horsemen of the apocalypse stumble while carrying a coffin. Line drawings inside the coffin indicate skeletal remains of people, homes and tawdry tourist pleasures. “Katrina’s Veil: Stand at the Gretna Bridge” pictures police who blocked exhausted Katrina refugees from walking to safety. Prince’s composition recalls a famous 1965 photo of police gassing and clubbing civil rights marchers in Selma, Alabama.

In “Katrina’s Dirge,” four horsemen of the apocalypse stumble while carrying a coffin. Line drawings inside the coffin indicate skeletal remains of people, homes and tawdry tourist pleasures. “Katrina’s Veil: Stand at the Gretna Bridge” pictures police who blocked exhausted Katrina refugees from walking to safety. Prince’s composition recalls a famous 1965 photo of police gassing and clubbing civil rights marchers in Selma, Alabama.

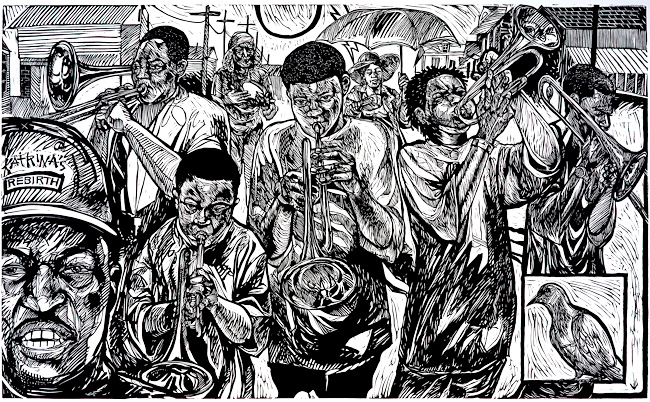

In “Second Line,” a rescue worker, who wears a hat labeled Katrina’s Rebirth, leads a brass band along a road lined with three crosses. A dove rests in a corner. Prince said that New Orleans natives release doves at weddings and funerals to invoke the Holy Spirit. People who can’t afford doves wave white handkerchiefs to simulate flying birds.

In “Second Line,” a rescue worker, who wears a hat labeled Katrina’s Rebirth, leads a brass band along a road lined with three crosses. A dove rests in a corner. Prince said that New Orleans natives release doves at weddings and funerals to invoke the Holy Spirit. People who can’t afford doves wave white handkerchiefs to simulate flying birds.

“Our lives are the dirge, the things we don’t want to talk about, which turn into diseases and kill us from the inside. The second line is the hopeful utopic place that we move to from hurt, shame and brokenness. The Bible comes alive when Christian artists use their art and the gospel to help us grapple with societal issues that plague us,” Prince said.

Their stories, our stories

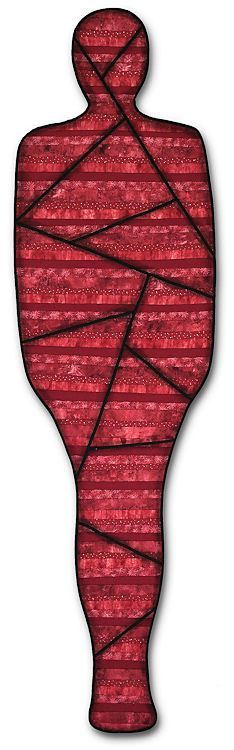

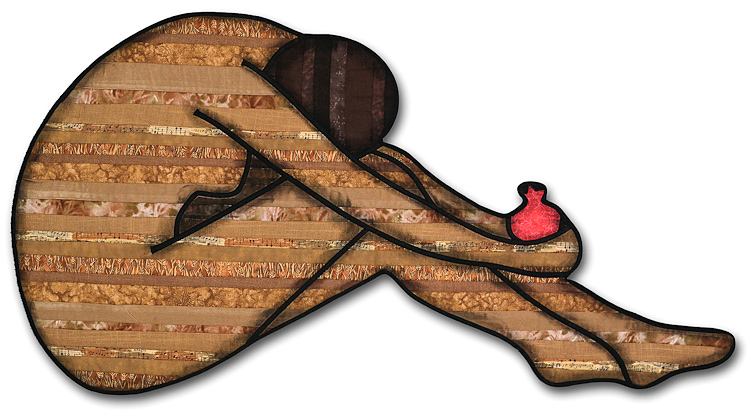

After pastoring two Lutheran churches, Linda Witte Henke wrote a book of Lenten meditations. “I decided to illustrate it so I could include women, even though the Lutheran lectionary doesn’t include women in Passion Week readings. The art got the most response. It seemed preposterous that God wanted me to be an artist—but now I’m a full-time liturgical textile artist,” she told “Who Is My Neighbor?” attendees.

Henke created Re-Membered: Mining the Untold Stories of Biblical Women for the conference, which was organized by Eyekons, an online marketplace for spiritually inspired art. Henke refers to the 13 fabric portraits as “the sisters. Each has closed eyes because women in biblical times weren’t allowed to look others in the face. They have no mouths because they didn’t have a voice,” she explained.

For each figure she wrote a brief narrative that ends with a way for viewers to “re-member” the woman. The Levite’s concubine (Judges 19:1-30) says, through Henke’s words: “Violence seems to always find a home in each generation….But re-member me by working tirelessly to bring an end to the violence.” Eve calls viewers to set aside past shames and reclaim “your identity as one fashioned in love and formed in the image of God.”

For each figure she wrote a brief narrative that ends with a way for viewers to “re-member” the woman. The Levite’s concubine (Judges 19:1-30) says, through Henke’s words: “Violence seems to always find a home in each generation….But re-member me by working tirelessly to bring an end to the violence.” Eve calls viewers to set aside past shames and reclaim “your identity as one fashioned in love and formed in the image of God.”

Portraying “the sisters” opened old wounds. “I’m a survivor of childhood sexual abuse. I’ve lived in 36 houses. I’ve struggled my whole life with loss, longing, scarcity and abundance. This series showed me that we all have these issues or resonate with someone who does.

“I appreciate working with fabric because it’s accessible. We sleep and wash with it. I pray, sing, recite Scripture and pour my heart out as I work—and it seems like people sense it. I’ve been surprised to see how strongly people react to visuals in worship,” Henke said.

Invitation to relationship

“I grew up in church. My mom gave me paper and pencils to keep me quiet. I attended all the services because I had to. But it became a choice, something I wanted to do, like answering Jesus, who stands at the door and knocks,” Sergio Gomez told conference participants.

At age 16, he moved from Mexico City, because his father accepted a call to pastor a church in Joliet, Illinois. “It was culture shock. I didn’t know the language but started school the next week,” Gomez said. Now he’s a painter, charcoal artist, art professor and gallery owner in metro Chicago.

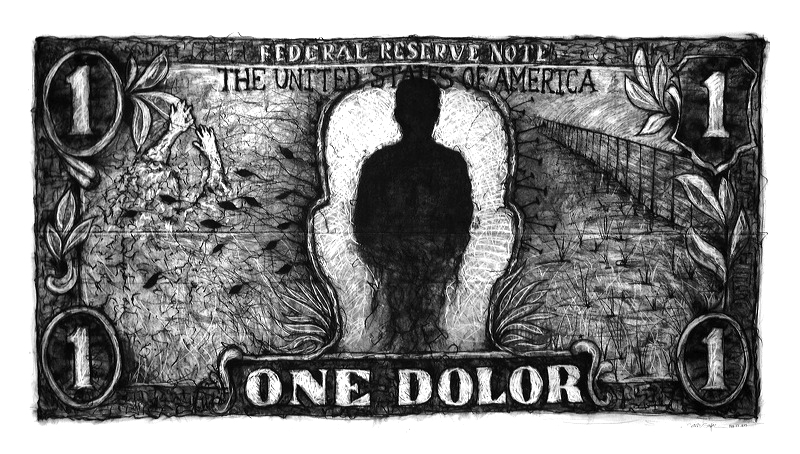

His work explores identity and spirituality, especially of people scorned as “other.” He painted “The Bleeding Border” after reading about children dying in the desert while trying to reach the U.S. It shows a boy and girl running hand in hand along a wall, caught in a Border Patrol helicopter spotlight. In his painting “One Dolor,” which looks like a U.S. dollar bill, a man stands between grasping hands and a fence. Dolor is a Spanish word for pain and suffering.

His work explores identity and spirituality, especially of people scorned as “other.” He painted “The Bleeding Border” after reading about children dying in the desert while trying to reach the U.S. It shows a boy and girl running hand in hand along a wall, caught in a Border Patrol helicopter spotlight. In his painting “One Dolor,” which looks like a U.S. dollar bill, a man stands between grasping hands and a fence. Dolor is a Spanish word for pain and suffering.

Gomez said he starts each work with writing and then draws and paints over most or all words. “Some things that I do not understand, I try to paint. The result is often a continued question rather than an answer. My work is very layered. In the process I discover things,” he said.

He often traces himself or his son to create ghostlike figures. “It’s a way of putting myself in the picture, but in a universal way that everyone can identify with. The chair for me is a symbol of someone missing or in an important chair, like, who’s in that one? The puertas abiertas, open doors, in my work are invitations to our vulnerability and a relationship with God,” he said.

Links

LEARN MORE

Don’t miss this story’s companion conversation, “Steve Prince on Visual Art and Justice,” about his large work entitled “Who Is My Neighbor?”

Eyekons organized the Who Is My Neighbor? conference and art exhibit. The conference included work from all artists quoted above.

Steve Prince and Linda Witte Henke will lead workshops and display their artwork at the 2015 Calvin Symposium on Worship.

See work in Steve Prince’s Katrina Suite. Explore the breadth of Linda Witte Henke’s work. She has five traveling exhibits and has work in several group traveling exhibits organized by Christians in the Visual Arts (CIVA). She recommends reading Jaroslav Pelikan’s book Mary Through the Centuries.

Besides teaching and creating visual art, Sergio Gomez owns 33 Contemporary Gallery, a socially- conscious fine arts gallery. Profits from the gallery’s 3c Wear clothing pay for basic school supplies for low-income schoolchildren.

START A DISCUSSION

Feel free to print and distribute these stories at your staff, education or worship arts meeting. These questions will help people think about what or who you’re not including in worship and how visual arts might help you address that absence.

- Which major life issues shape your worshipers’ lives—but are rarely mentioned or pictured in worship?

- What people groups in your congregation or church neighborhood don’t appear upfront leading worship or in your worship space or in imagery used in your worship?

- What visual first step could you take to get people talking about how God’s story connects with the issues or people you’ve till now not included?