By all accounts, Mary Aluel Garang has never sought the limelight. She was born into a traditional cattle-herding Dinka family in about 1966 in what is now Jonglei, a state in South Sudan. The Dinka are South Sudan's largest people group. Mary Aluel became a Christian in 1984, early in the Second Sudanese Civil War. Soon after, she began composing theologically rich songs in the Dinka Bor dialect.

She kept writing despite moving several times for safety and education before South Sudan gained its independence in 2011. Throughout her life, whether focusing on theological education or women's development, she has continued to write hymn texts.

Anglican/Episcopal and other Sudanese Christians around the world still sing Mary Aluel Garang's hymns because her words help them locate themselves within the story of God. Singing her songs helps them make sense of the conflicts that continue to displace, maim, and kill people in South Sudan. In fact, scholars have described Mary as "a gifted natural theologian" and "the Charles Wesley of the church of Sudan."

A note on names: This hymnwriter has been variously described as Mary Aluel, Mary Alueel, or some combination of Mary Aluel Garang (her father's name) Nongdit (nickname of great respect meaning "great feather") Anyuon (her paternal grandfather's name).

From the margins

While many books about Sudanese Christianity mention Mary Aluel or use phrases from her songs as book or chapter titles, two books by North American Episcopalians help form the clearest picture of her life.

"Mary . . . is from a family with a tradition of traditional compositions. Her language and idioms are extremely rich, deeply rooted in the rural language of her . . . people," Marc R. Nikkel wrote in Dinka Christianity: The Origins and Development of Christianity among the Dinka of Sudan with Special Reference to the Songs of Dinka Christians. Nikkel was an American Episcopal priest who worked among the Dinka for twenty years. He translated many songs by Mary Aluel and other Dinka Christians into English.

In traditional pre-Christian Dinka culture, girls and women rarely created songs. They had to stay silent and seated during family discussions. They were valued mainly for growing millet and vegetables during the rainy season, earning a high bride price in cows, and producing sons who could increase herd sizes. The Anglican missionaries who came from the United Kingdom in 1899 to educate a cadre of indigenous Dinka evangelists did not invite girls to study in mission schools.

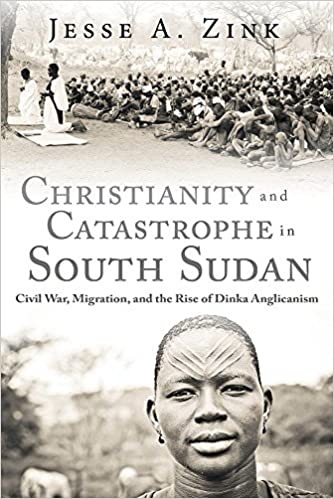

Somehow, Mary Aluel briefly attended school as a young girl in Malakal, a city along the banks of the White Nile. But she was "taken, snatched from the town, to be taken home. At that time, the Dinka say, 'Our girls cannot be in towns. We need our girls to be in the cattle camps,'" she told Jesse A. Zink in 2013 while he was doing extensive fieldwork to write Christianity and Catastrophe in South Sudan: Civil War, Migration, and the Rise of Dinka Anglicanism. Zink, an Anglican/Episcopal priest and author, is now principal of Montreal Diocesan Theological College in Montreal, Quebec.

The Dinka remain proud of their legendary cattle herding culture and wrestling prowess. They orally transmit ancestral values through songs and sayings. But even during Mary's childhood, several factors—unusual flooding, widespread cattle disease, and the First Sudanese Civil War (1955–72)—forced young men to leave home. Many learned to read and write in Dinka and in English and became Anglican Christians. Zink explains that Dinka culture stayed focused on cattle camps, villages, and shamans of local divinities called jok (singular) or jak (plural). Christianity remained a minority religion, something for the young, urban, educated, and elite. But the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005) changed all that.

Displacement creates space for women

The roots of Sudanese civil conflict included the aftermath of British colonialism; ethnoreligious conflicts between the Arab Muslim north and animist/Christian south; disputes over water, fertile land, and oil deposits; and political and intertribal rivalry.

The Second Civil War displaced people from towns and cities back to villages and cattle camps. They brought their faith and songs with them. Mary learned about Christianity from young people who moved to her village from the market town of Bor, on the east bank of the White Nile River. Zink writes in a blog post that this pattern of urban Christians bringing the faith to rural people was repeated all along both riverbanks, from Juba north to Khartoum.

When Mary converted and was baptized in 1984, "she was divorced, and her only child had died. This put her in an unusual and almost powerless position in Dinka society. Today, however, she is widely recognized in the Dinka church and beyond," Zink writes in Christianity and Catastrophe. That so many Dinka Bor people became Anglican during the Second Civil War is due partly to a decision by Bishop Nathaniel Garang Anyieth (no relation to Mary) to stop requiring literacy as a condition of baptism.

Zink explains in his book that the Church Missionary Society (CMS) had for generations required baptismal candidates to study for a year or more until they could prove they knew enough about Christianity. Growing up in an oral culture, the Dinka were very good at memorizing, and missionaries suspected that they were "cheating" by simply memorizing rather than reading the necessary passages and answers. They worried that baptized Christians wouldn't be able to deepen their faith without literacy .

But for five years during the Second Civil War, the people in the Bor region were cut off from the rest of the Anglican Church. Bishop Nathaniel was the only bishop in Bor, and thousands of Dinka Bor wanted to switch allegiance to a God more effective than their local jak. So the bishop decided to baptize first and train and catechize later.

All these changes created a kairos moment for Dinka women to meet and encourage each other through worship and church meetings and to share learning in their preferred cultural way: singing.

Songs from scripture

Like Christians around the world, many Dinka Anglicans began learning the Bible and theology through songs. Meditating on scripture inspired Mary Aluel to compose hymn texts. In 1985, the year after her conversion, she wrote two songs that quickly spread widely, according to Nikkel.

The first, "Death Has Come," spoke to people as warring groups stole their cattle, burned their homes, destroyed jak shrines, raped and killed their relatives, and forced them to flee. When this song was published in the first hymnal edited by Dinka Anglicans, the editors gave John 11:25–27 as the scriptural reference. "Death Has Come" is the first song that Mary Aluel sings on what's described as "Aluel Garang Anyuon's Classic Album." That's according to Luke Bol Majak, the current elected parish secretary of St. Luke's Church, Ngumo-Dinka congregation, a diaspora Episcopal Church of South Sudan congregation in metro Nairobi, Kenya.

The first of four long verses begins: "Death has come to reveal the faith." The hymn gives voice to suffering and pleas, as in verse three: "God, do not make us orphans / of the earth. / Look back upon us, / O Creator of humankind. / Evil is in conflict with us." The final verse begins: "Let us encourage our hearts / in the hope of God, / who once breathed wei [breath and life] / into the human body. / His ears are open to prayers: / the Creator of humankind is watching."

The second early song that spread was "God Has Come Among Us Slowly" (p. 9). Mary Aluel wrote it and "Death Has Come" in Kongor, which had a brief flurry of Christian revival in the late 1940s and early 1950s, according to Zink's book. Meanwhile, other people groups in southern Sudan responded far more enthusiastically to Christian missionaries than the Dinka did.

The first of five verses begins: "God has come among us slowly, / and we didn't realise it. / He stands nearby, behind our hearts, / shining his pure light upon us." The song explains that God, not jak, created all people and all things, even the insects. It asks for the Lord's power and "Guiding Spirit of truth" to reach everyone, and it muses, "We receive salvation slowly, slowly, / all of us together, with no one left behind (v. 2). . . . Gradually, gradually it will succeed, / until the day when it will be grasped / by the Dinka who sacrifice at shrines (v. 3)."

"Natural theologian"

What are now Sudan and South Sudan overlap the area known in ancient times as Nubia, Kush, or Cush. Early CMS missionaries drew parallels between biblical references to Cush and the Dinka people, especially Isaiah 18, which mentions tall, smooth-skinned warriors in a land divided by rivers.

That chapter wasn't included in the hundred Old Testament passages that Archibald Shaw and other CMS missionaries translated into Dinka before World War II. But the first British edition of the Good News Bible paraphrase gave Isaiah 18 the chapter heading "God Will Punish Sudan." Nikkel, Zink, and other scholars explain that Isaiah 18 became a keystone passage to help the Dinka understand their suffering. (Compare Isaiah 18 versions in this Zink presentation, slide 10.)

Many Dinka Christians believed Isaiah 18 foretold that great suffering would purify the Dinka to reject the jak and return to Nhialic, the Creator God known already in their traditional religion. Then God would bless them, and they'd gain national independence (a "signal raised on a mountain," v. 3). Mary Aluel's most famous song of all, "Let Us Give Thanks" (also known as "Day of Devastation, Day of Contentment") expresses that confidence and hope. (Listen to the song in Dinka.)

Nikkel says Mary composed "Let Us Give Thanks" after being displaced yet again, first after the November 1991 Bor Massacre and then in July 1992 after government forces captured the town of Torit, near the Ugandan border. The song frames devastation as part of God's plan: "Evil is departing and holiness is advancing; / these are the things that shake the earth" (v. 1). It calls people to "remove hatred and the stubbornness of hearts bound by sins" (v. 3), to "do what you are able to do / according to the gift which / has been given you" (chorus), and to "let the name of God be praised" (v. 6).

Nikkel describes Mary Aluel as "perhaps the finest composer of her era, certainly among the Bor Dinka, and likely the most gifted 'natural theologian.'" He wrote that when the Archbishop of Canterbury visited Nimule in southern Sudan in early 1993, the people sang "Let Us Give Thanks" after each of his addresses.

In the February 2017 issue of Sudan Studies (pp. 12–21), Zink analyzes the Bung de Diet ke Duor (BDD, or Book of New Songs of Worship), a Dinka-language hymnal created by members of the Diocese of Bor of the Episcopal Church of the Sudan in the 1990s. The BDD songs are divided into "choruses" (496) and "long hymns" (164). Forty-three percent of its songs were written by women. Of the nineteen women composers, Mary Aluel contributed nine long hymns—the most of any composer in the BDD. "It is these hymns that have done so much to shape the theology of Dinka Christianity and which are sung with such fervour by Dinka Christians today. . . . Although the hymnal was written in the Bor dialect, it was used throughout the Dinka Anglican church," Zink writes.

Still singing for peace

"I think I met the Charles Wesley of the church of Sudan," Jason Byasse wrote in a Faith & Leadership blog post in 2010. "Just as Charles’ hymns powered the Methodist movement across the British Isles, the Americas, and now the Global South, so too did Mary Aluel Garang’s songs power a revival in the Episcopal Church of Sudan (ECS), helping to bring in millions of members during that country’s brutal two-decade long civil war." By then, Mary had managed to get five years of theological education in Kenya, "as much as any leader I met in the ECS," Byasse reported.

In the 2010s, Mary Aluel's work focused on girls and women. As director of a church and development office in gender equity, she convinced many parents in the Bor Diocese to send their daughters to school. As women's ministry director for Partners in Compassionate Care, she taught women how to read, use a solar-powered "talking Bible," access healthcare, start businesses, and work for peace (p. 3). She has continued to teach and occasionally write hymns. She is married to Daniel Chagai Gak Deng, an ECSS priest, and lives in Juba, the capital of South Sudan.

In South Sudan, as in other places, identity politics are polarizing churches and nations. Yet, Mary Aluel Garang has remained known for focusing on what unites people.

"In most countries around the world, politics has managed to overshadow faith. Once you appeal to people's emotions politically, they are likely to react. The people of South Sudan have been divided along tribal lines and made to believe that true liberation for them is attached to tribal identity. Not all are able to appreciate that Christian faith binds them to people with different tribes and politics," Lual Mayen-Adiit said in a February 2022 Zoom call. He coadministrates the St. Luke's Church webpage and is head of the Jol Wo Lieech (Look back on us, God) hymn-teaching branch for all of Nairobi, Kenya.

"Mary Aluel comes to St. Luke's whenever she is in Nairobi," Lual Mayen-Adiit said. "She still writes hymns and songs. She is as strong in faith as ever. Some people write songs to be creative, as if writing a song does God a favor. Mary Aluel's songs flow out of prayer, and her themes transcend generations. One of her recent songs talks about forgiveness. It asks us to displace the spirits of hate and revenge and move forward."

LEARN MORE

Find Marc R. Nikkel's work on WorldCat byentering your location to help you locate the nearest library with a copy of Dinka Christianity: The Origins and Development of Christianity among the Dinka of Sudan with Special Reference to the Songs of Dinka Christians. Also read Why Haven't You Left?: Letters from the Sudan, by Marc R. Nikkel and Grant Lemarquand.

Read Christianity and Catastrophe in South Sudan: Civil War, Migration, and the Rise of Dinka Anglicanism by Jesse A. Zink. Learn the English meaning of many Dinka words.

Vince Bantu is an expert in African Christianity who now teaches at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California. Starting in the fifth century CE, he explains, the Nubians maintained an indigenous Black Christian kingdom for nearly a thousand years. By the 1400s, however, Islam prevailed.

Medieval Arabs referred to the countries south of the Sahara Desert as "the Sudan bilād al-sūdān (“land of the blacks”).

A March 2018 photo story in The Guardian shows that cattle remain important in Dinka culture. This New Humanitarian story and these Better Samaritan blog posts (food aid, education, refugee camps) show why life remains challenging for many people of South Sudan.

For updated prayer needs among Dinka Christians and others in South Sudan, sign up for monthly free emails from The American Friends of the Episcopal Church of the Sudans (AFRECS).

To learn how race and Christian faith can unite or divide people, read Chosen Peoples: Christianity and Political Imagination in South Sudan, a history & biography finalist in Christianity Today's 2022 Book Awards. Christopher Tounsel, the author of Chosen Peoples, is a historian of modern Sudan and teaches history and African studies at Pennsylvania State University.

START A DISCUSSION

Feel free to print and distribute this story at a meeting of your staff or board or of your education, worship, or outreach committee. These questions will help people start a conversation about South Sudanese Christians and worship music that deals with real-life issues:

- Describe your knowledge about or connections with Christians in or from South Sudan.

- Which songs in your congregation's repertoire speak specifically about joys and problems in your culture or subculture?

- How can you tell when your political or cultural identity overrides your "one Lord, one faith, one baptism" identity? Which of your worship songs address this issue?