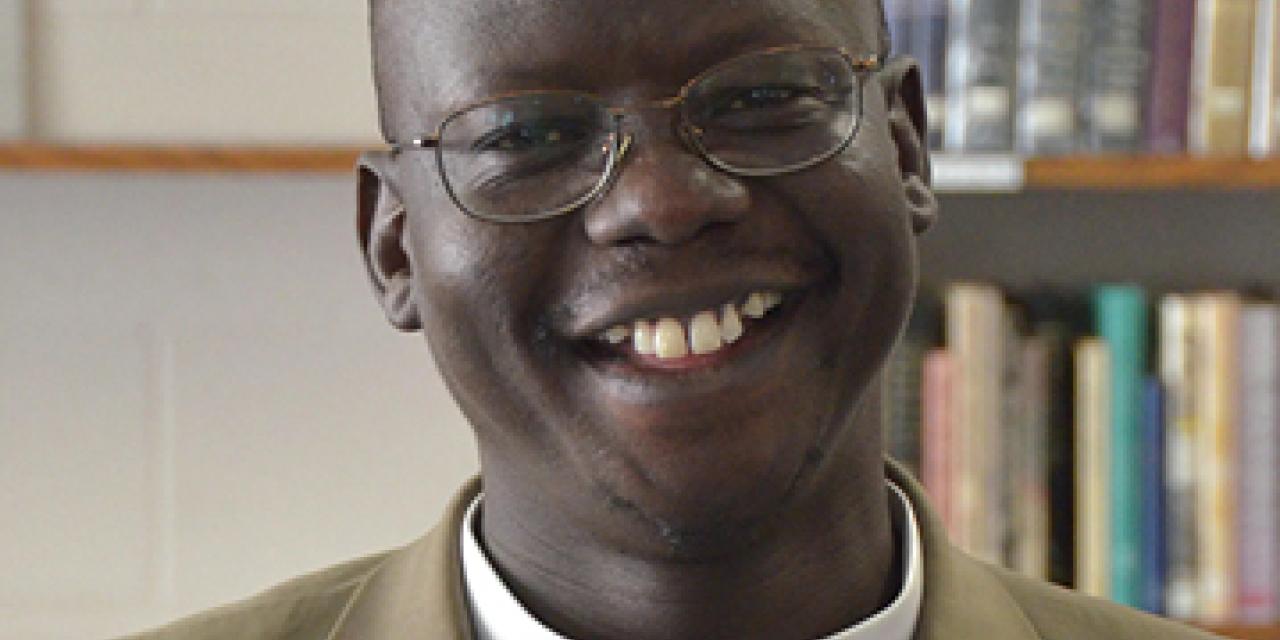

At age three, Zachariah Jok Char started learning the Dinka alphabet during Sunday school at the Episcopal church in his Sudanese village. "My family was one of the earliest to become Christian in our village of Duk Padiet,” he says. “My father loved to sing. He had a lot of cows and goats because he was a hard worker. But he always said that you cannot succeed in life without knowing God. My mother was special. She didn't get mad easily. She loved God, and all the people loved her."

By age five, Char was reading in Dinka Bor, a dialect spoken by the largest tribe in what is now South Sudan. He remembers singing new songs by Mary Aluel Garang, whose songs helped inspire a revival among the Dinka during the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005). "We learned by hearing songs written out by hand," Char recalls.

His secure life in the Dinka culture of cattle herding, wrestling, and songwriting disappeared in 1987, when soldiers from northern Sudan attacked. "My parents and older siblings were in the fields. I was playing with my agemates. I heard shots and hid by a pond. I spent a night in a tree. Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) soldiers found me and other hidden children," Char says. The SPLA led Char and others on a thousand-mile walk to a refugee camp in Ethiopia. Thousands died because of malnutrition, heat, thirst, lions, crocodiles, drowning, infection, and bombings.

Three years later, the Ethiopian government fell, and the children fled back through Sudan to Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya. Char, who became part of the group known as the "Lost Boys" of Sudan, is now the rector of Sudanese Grace Episcopal Church in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

During his long years in refugee camps, Char says, the church gave him "a glimmer of hope" that God had a purpose for his life. The Jol Wo Lieech song ministry and Thiec Nhialic prayer ministry provided the church infrastructure at refugee camps like Kakuma, which in Swahili means “nowhere.” Those two groups still help Christians in South Sudan and in diaspora congregations to build faith through singing and working for intertribal peace.

Indigenous song ministry

Marc R. Nikkel, an American Episcopal priest, lived among the Dinka for twenty years and wrote Dinka Christianity: The Origins and Development of Christianity among the Dinka of Sudan with Special Reference to the Songs of Dinka Christians. In the 1960s, Nikkel writes, two Dinka Episcopal priests began using the phrase jol wo lieech, which means “Look back on us, God.” They felt left behind by God as other tribes more widely became Christian and literate.

In the 1980s, as civil war uprooted Dinka life, people used the phrase jol wo lieech to ask God to address their suffering. Young men started forming Jol Wo Lieech (JWL) groups to compose and teach songs. Using traditional Dinka song forms for new gospel hymns helped Christian faith spread rapidly. These youth and young adults brought their faith and new songs to refugee camps in Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda. (Alternative spellings for JWL include Jol/Jo and Liec/Lieec/Liech/Lieech.)

"In Ethiopia, we had a small church in a fenced-in area," Char says. "I began learning the English alphabet in Ethiopia. We had no books, so we drew in mud. In Kakuma, life was even harder. The UN [United Nations] gave us only grain and oil rations, barely enough to survive. I didn't know where my family was. I had no way to make a garden or business. All I had was school and God."

At age eight or nine, Char began helping to organize worship services and teach people to read Dinka. He remembers singing Dinka gospel songs "at Sunday services, morning and evening prayers, and Friday youth services." Eventually Char served as a lay pastor and preacher in a large congregation at Kakuma.

In Christianity and Catastrophe in South Sudan: Civil War, Migration, and the Rise of Dinka Anglicanism, Anglican/Episcopal priest Jesse A. Zink explains that only young, unmarried males active in church could join JWL. "For many young people who were separated from their families, . . . JWL gave an important sense of community that they were lacking elsewhere," Zink writes.

Marc Nikkel recounts in a 1994 letter how Episcopal priest Stephen Dit Makok [also known as Diit Magok], who compiled the first indigenous Dinka Bor hymnal, held nightly song teaching sessions at Kakuma. "I learned all 662 songs," Char says.

Praying for peace

Traditional Dinka religion centered on male prophets or shamans who sacrificed to the jak (local gods). But as Christianity spread and men went to (or fled from) war, women found leadership opportunities in the church. They formed an affinity group called Thiec Nhialic (TN), which means “to ask (or beseech) God.” (Some sources spell it Thiech Nhialic.)

TN combined prayer and action. Zink writes that these women composed and taught Christian hymns, preached, and "were at the forefront" of praying for God's protection. They taught young refugee boys to make bricks for building, cook for themselves, and care for their physical health. While teaching youth how to make dressings and give injections, TN reminded them to ask God for healing and offer thanks in church for answered prayers.

Rebecca Deng, an orphan at Kakuma, found relief from the tedium and deprivation of refugee-camp life when women invited her to walk thirty minutes to church to pray, dance, sing, and learn about Jesus. "It was just a few simple rows of raised mud for people to sit on with a fence around it, but it was filled with people who all seemed kind and happy!" she writes in What They Meant for Evil: How a Lost Girl of Sudan Found Healing, Peace, and a Purpose in the Midst of Suffering.

Soon the women invited her to beat the drum that called women and girls to Tuesday prayer meetings. "They prayed for refugee children, the war, and changes they were seeing in so many people. . . .They were real; they didn't try to hide how they were suffering, and the other women comforted them," Deng writes.

Zink and Nikkel describe massive TN campaigns at Kakuma where women prayed, sang, and marched during a cholera outbreak and after the UN cut food rations. "The cholera epidemic ended and rations were restored after the 1997 actions. More broadly, members of Thiec Nhialic came to believe that their activity created the conditions for the end of the war," Zink writes.

Working together

JWL and TN have remained important for South Sudanese Christians whether they're still in refugee camps, have returned home, or have formed diaspora congregations in other countries. Both organizations have specific responsibilities, yet often collaborate between branches or organizations.

In JWL, Alooŋ (Aloong) collects, documents, vets, and teaches new songs and helps create hymnals. AGAYTH (Akutnhom de Gäär Athöör ku Yiknhial de Thuɔŋjäŋ) is responsible for Dinka language learning and literacy education—crucial for people who can't find places in schools. Luäŋyic (Luängyic) helps translate and teach the Bible. Lëk is responsible for evangelism.

TN's three divisions are Tukinhiɔl, (prayer), Youth Mama, (evangelism and organization), and Planning Committee, (fund mobilization and planning). Though founded by older women, TN now includes young men who help run its Youth Mama choir program. Note to copyeditor: it was important to Lual Mayen-Adiit that I use the Dinka characters and spelling to describe the JWL and TN divisions.

Zachariah Jok Char says that, especially since South Sudan became independent on July 9, 2011, many JWL members, Lost Boys, and Lost Girls have returned on mission trips or to live. They are active in the Episcopal Church of South Sudan (ECSS), the government, health care, education, and other societal structures. JWL and Youth Mama groups in Australia help fund recording projects in East Africa. Yet life in South Sudan remains difficult. Climate change causes horrific flooding. Violence erupts among the nation's 60+ ethnic groups.

JWL and ECSS have run peacemaking campaigns together. In the 2010s, TN's Youth Mama choirs gave multilingual concerts and produced video albums of South Sudanese people singing Christian songs in their own languages. For example, this 2015 multilingual video song album calls people to find their unity in Christ. Unfortunately, political divisions made along ethnic lines have disrupted Youth Mama's intertribal freedom.

Char takes a long view: "The nation and church don't have enough resources to fix roads, create banking systems, open schools, or train pastors. But the church is still where you find love and care. South Sudan is still a baby nation. One hundred years from now, life may be better. Just think about how long it took for the United States to end slavery. And when George Floyd was killed, we saw that police still sometimes mess up and use violence."

Labor of love

For Char and many people connected with JWL and TN, singing together about God's power and love is one of the best ways forward. St. Luke's Church, Ngumo-Dinka congregation, an ECSS diaspora congregation in metro Nairobi, Kenya, is a key conduit for teaching Dinka hymns.

Lual Mayen-Adiit co-administrates the St. Luke's webpage that livestreams Sunday worship services and hymn teaching sessions. "Our congregation has people from all walks of life. I have been a teacher in the ECSS for twelve years, teaching Dinka dialect, Bible study, hymns, and basic social issues," he said in a February 2022 video call also joined by webpage co-administrator Luke Bol Majak.

Lual Mayen-Adiit also heads the Alooŋ (Aloong) branch of JWL in Nairobi. "JWL is mandated by the ECSS to collect, edit, analyze, teach, and record songs," he says.

"Songwriting is still important in Dinka culture," he adds. People still make songs for courtship or to appreciate someone who does something nice for them, however small. And new Christian songs are still coming in fast and furious to JWL. The work is infinite because we need to choose, edit, sing, record, produce, and post gospel music videos. We need people to help polish the inspirations of others, but we have fewer volunteers now, because so many people have moved away from the active ministry to work in other sectors so as to sustain their families."

Luke Bol Majak, the current elected parish secretary of St. Luke's, runs the Dong-Rin Publishing YouTube channel so that people can learn the hymns by earhearing. Seeing the words on screen while hearing them also helps people improve their Dinka literacy. "My late dad, Gabriel Majak Bol Majak, was a gospel writer and composer who has around nine songs in the old Dinka hymnal,"” Bol Majak says. "He and eighty-eight others were killed in civil war on 20th October 2013. The name Dong-Rin was from my dad."

Like songwriter Mary Aluel Garang, JWL members see the songs as cooperative products, not music that someone is meant to financially profit from. "I give the songs to the church because they are God's songs, not mine. . . . They come from the Lord, passing through my mind," Mary Aluel said in this 2011 BBC Sounds program about the music of South Sudan [15:00–16:31]. When the Spirit gives her a song, she explained, she brings it to JWL "so that we may sing together and correct the song, and then they may take it to the churches."

In the February 2022 video call, Lual Mayen-Adiit sang the fifth verse of a song that Mary Aluel wrote in 2018, then gave a spontaneous English translation of that stanza: "We come before you, God, to thank and worship you for the love you have shown us by sending our Savior to us on earth, Jesus Christ, who volunteered to suffer and died for sins he did not commit. He owned our transgression so as to restore the dignity of the initial plan that God had for man, so that man may live as God had initially thought."

After translating this stanza, he said, “It sounds even more inspiring than I had been thinking for the last three years."=

Three links to go in Find More Box:

- Accompanying feature story "Mary Aluel Garang: The Charles Wesley of South Sudan"

- Accompanying conversation "Karen Campbell on Dinka Gospel Songs"

- https://worship.calvin.edu/resources/resource-library/emmanuel-olusola-fasipe-on-yoruba-baptist-indigenous-choruses/

LEARN MORE

The New York Times, Episcopal News Service, and the short film Lost Boy Home profiled Zachariah Jok Char, now rector of Sudanese Grace Episcopal Church in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He welcomes contact from anyone who wants to buy a print copy of the current Dinka hymnal, help pay for a medical clinic in Duk Padiet (his native village), share resources or information on how to provide theological training for pastors and deacons in South Sudan, or partner to bring Mary Aluel Garang to the U.S. for a hymn workshop.

Funding from JWL in Australia and elsewhere is underwriting some costs of producing the next Dinka Episcopal hymnal. Luke Bol Majak says that song drafts from 2013, 2017, and other years are helping people learn new hymns. They learn orally because there's no standard system for notating Dinka music and because many people in South Sudan are not yet literate. But people who teach the new songs from memory may use different words, tempos, or notes. This March 9, 2022, Facebook post by Simon Yak Deng details efforts to standardize songs being considered for the new hymnal. "Simon Yak Deng is a songwriter and vocalist like no other I have seen. He will have in excess of forty songs in the new hymnal," Lual Mayen-Adiit said in a February 2022 video call.

Read and research more about Christianity in South Sudan:

Books

- Chosen Peoples: Christianity and Political Imagination in South Sudan, by Christopher Tounsel

- Christianity and Catastrophe in South Sudan: Civil War, Migration, and the Rise of Dinka Anglicanism, by Jesse A. Zink

- Dinka Christianity: The Origins and Development of Christianity among the Dinka of Sudan with Special Reference to the Songs of Dinka Christians, by Marc R. Nikkel. (Enter your location so WorldCat can help you locate the nearest library with a copy.)

- Why Haven't You Left?: Letters from the Sudan, by Marc R. Nikkel and Grant Lemarquand

Journal and web resources

- "History of Christianity in Sudan," by Andrew A. Wheeler in Dictionary of African Christian Biography

- "Lost Boys Found" is an ongoing interdisciplinary project at Arizona State University that collects, records, and archives the oral histories of the Lost Boys/Girls of Sudan.

- The New Sudan Council of Churches published many resources to help end the Second Sudanese Civil War.

- Sudan Studies is a twice-yearly, non-peer-reviewed journal based in the UK.

- This multilingual video song album from 2015 calls people to find their unity in Christ.

Current news and prayer needs

- The American Friends of the Episcopal Church of the Sudans (AFRECS) offers free monthly emails to help you pray for South Sudan.

- United Nations news on South Sudan gets updated often.

START A DISCUSSION

Feel free to print and distribute this story at meetings of your staff, board, or committees for education, worship, or outreach. These questions will help people start a conversation about South Sudanese Christians and finding unity through music and prayer:

- Describe your knowledge about or connections with Christians in or from South Sudan.

- How involved are your congregation's lay people in creating, choosing, or voicing the sung or spoken words used in worship?

- What groups within your worshiping community or church tradition give you hope that God still has a purpose for you and your congregation?