Penny. Bridesmaid dress. Roast in a Crock-Pot. These are not things that require deep thought. You know what each is for.

But imagine walking into church one Sunday to find a woman handing out pennies. Or what if you spotted bridesmaid dresses or a fragrant slow cooker in the narthex? You’d probably look at worship that day with fresh eyes, wondering how to interpret those surprising elements and pondering what they could possibly have to do with you and God.

Mark Moeller, now a pastor at First Baptist Church in Knoxville, Tennessee, once planned a parable of the lost coin worship service that began with a woman distributing pennies before the prelude. He suggests using the dresses or roast to invite worshipers into parables about the foolish bridesmaids or great banquet.

When Jesus started telling stories about ordinary things such as seeds, bread, or sheep, or common situations, such as a boss and worker, people smiled and relaxed. They figured they knew where the story was going. Likewise, when headlines apply “good Samaritan” to people who rescue stray dogs and stranded boaters or “prodigal son” to comeback athletes and senior bankers returning to Wall Street, we think we know exactly what Jesus’ parables mean.

However, just as Jesus told parables with surprising twists, you’ll want to plan parable-based worship that reverberates after the service ends. It’s also vital for worship leaders, musicians, and preachers to plan together so people experience the parable as far more than a good reminder.

Fresh eyes

The way Jesus told stories let him sidestep people’s prejudices and self-perceptions. Clarence Jordan, whose Cotton Patch Gospel is a folksy Southern translation, compared Christ’s parables to a Trojan horse. The Message translator, Eugene Peterson, describes the parables’ indirect relational approach as “telling it slant.”

The ways that Jesus used language and that the gospels present his parables give clues to mine more meaning.

Start with context, gradually telescoping your view from chapter and Hebrew Scriptures to culture and church tradition. The gospel reading (Luke 15:1-3 and 8-10) in Moeller’s lost coin service preserves how Luke framed the parables of the lost sheep, lost coin, and lost son(s). Jesus told these parables in response to Pharisees who were grumbling that he welcomed and ate with tax collectors and sinners.

Just as “nine-one-one” now triggers collective memory, when Jesus told stories about shepherds and vineyards, his listeners recalled shepherds and vineyards in the Psalms and Prophets. Parables about banquets, garments, kings, servants, and weddings also sparked connections.

Consider the original setting, which included both Jewish and Greco-Roman cultures. The parables assume dozens of “goes without saying” realities of Middle Eastern village life. Books by New Testament expert Kenneth E. Bailey reveal Middle Eastern nuances that unlock gospel meaning. Before you automatically dismiss allegorical tradition, read how the early church interpreted parables.

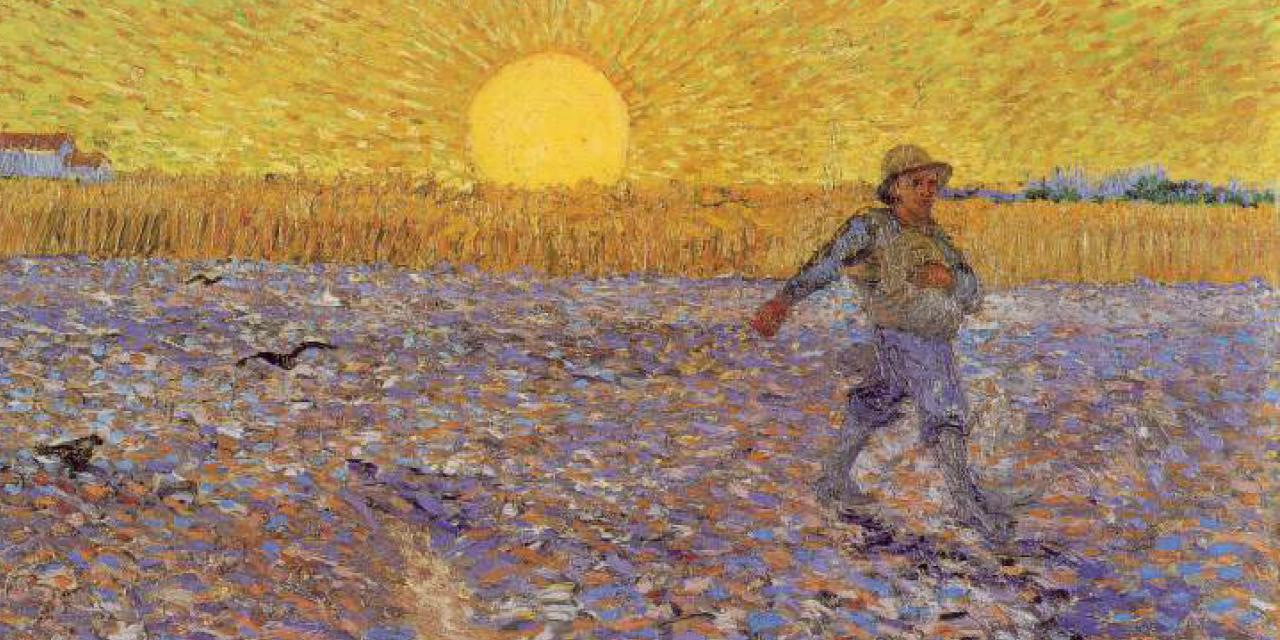

Another great way to get at clusters of meaning in a parable is to look at the story from several points of view (e.g. sower, seed, birds, soil types, or crop). In Moeller’s lost coin service, the surprise comes in seeing the coin as a cast-aside person made in our Savior’s image—so that if you go looking for the lost, you will find Christ.

Embrace ambiguity

Sometimes the gospels explain a parable, such as when Luke prefaces a story about a widow and judge with “Then Jesus told his disciples a parable to show them that they should always pray and not give up.” Yet right up till he died, the disciples often didn’t get his stories.

So don’t be discouraged when—after taking time to understand a parable’s central intent and let its other aspects leaven your imagination—you still have questions. Why does Matthew’s gospel present Jesus as nonviolent yet include eight parables in which God deals violently with evildoers? Why do some parables present God as a king who acts and others as someone who waits? What does that mean for your prayers?

Most of all, how do you embrace the risk of ambiguity, the tension between the story’s original context and its authenticity today?

Remind yourself that tension in the parables and Christian life “is not like a tightrope where we must fear falling off either side,” New Testament scholar Klyne Snodgrass assures in Between Two Truths: Living with Biblical Tensions. It’s more like a stringed instrument with strings properly placed and stretched to make music. The parables play Christian life as a rhythm of God comforting and disturbing, comforting and disturbing. “If grace tells us, ‘You are God’s child,’ it also instructs us, ‘Now live like it,’ ” Snodgrass writes.

Enter the story

You already know it’s much easier to affirm beliefs or prescribe behaviors than to live them. In an interview about his hefty Stories with Intent: A Comprehensive Guide to the Parables of Jesus, Snodgrass says, “I realized how easy it is for all of us to hear but not perceive, to see but not notice, and to acknowledge but never perform."

That’s why, as Eugene Peterson says in Tell It Slant, you can’t understand a parable as a spectator. The only way to get it is to participate in the story by taking on a role. Peterson says that God’s word personally addresses, invites, comforts, and rebukes—but never coerces. Jesus never forced anyone to recognize themselves in a parable. He simply told stories.

If you’re tempted to reduce a parable from “language that welcomes mystery” to a handy slogan or good example, then try this. Picture the parable as a faceted diamond sparkling with color as you turn it over and around in the light. Or imagine each parable as a treasure chest from which you can bring out old and new things.

When you let the parables work in conversation with your life, the Holy Spirit may surprise you with new insights. It happened to Christianity Today editor Mark Galli when he spent a rainy Saturday in Manila, happily reading about Karl Barth. He had no idea that far below his ninth-floor hotel room, Typhoon Ondoy was swamping slums, destroying lives.

Later Galli wondered whether the Levite and priest ignored the mugging victim not because they didn’t care—but because they didn’t practice the imagination and attention that the Good Samaritan did. “It's pretty hard to ignore human suffering right before your eyes. But it's pretty easy not to see it in the first place,” he writes.

Choosing music that preserves a parable’s twist

Martin Tel, now music director at Princeton Theological Seminary, remembers one of the first daily chapels he helped plan there. “We asked the student what he’d be preaching on. It was the parable of the good Samaritan. We all knew the story so we went straight to the student’s ideas and started planning music.”

A few years ago, an interim minister of the chapel suggested two small changes in how Tel and his team planned daily chapel worship. “I look back now and see that those little changes in the pattern made all the difference in the world. Now our worship services have more integrity. They are more honest,” Tel says.

You can use Tel’s insights to plan parable-based worship that is truly scriptural and includes music that preserves the parable’s twist in ways your congregation can sing and remember.

More power to the Word

Tel remembers the interim minister of the chapel saying, “We know we all have ideas for this worship service but let’s suspend those for now till after we open with prayer and read the Scripture out loud.”

The planners had always had their Bibles open on their laps before, yet, Tel says, “If someone reads the passage out loud, more power is given to the Word and less to the planners. After prayer and the reading, we return to the table with our ideas.”

“If someone reads the passage out loud, more power is given to the Word and less to the planners. After prayer and the reading, we return to the table with our ideas.”

This approach is especially helpful with parables, because people tend to assume they know what the familiar stories mean. The chapter subtitles that translators add to the gospels (The Parable of the Shrewd Manager, The Parable of the Prodigal Son) reinforce the idea that each parable has a single message for all times and places.

“Some hymns and songs about parables too neatly summarize or hone in on ‘the’ meaning. The titles aren’t wrong, just narrow. They may get at the preaching kernel, but is that the most effective way to get the congregation to respond?” he asks.

Finding out where the preacher is going with a parable is crucial. “If the sermon brings us to a new insight not common with this parable, then we want songs that fit. The parable hymn ‘Far from Home We Run, Rebellious’ puts us in the story and identifies ‘we’ with the Prodigal. It doesn’t work as well with a ‘begrudging brother’ sermon focus,” Tel says.

Frame the songs

When he and Princeton homiletics professor Luke Powery planned a parable service at a recent Calvin Symposium on Worship, Powery “didn’t want us to get sidetracked by the title ‘The Persistent Widow.’ The theme became the gracious merciful judge who loves us as much as a mother. That theme directed us to a new musical response,” Tel says.

He looks at the Psalms as “musical partners of the parables.” The musical call to worship in their symposium parable service included “The Lord Will Hear the Just” (Psalm 34 et al.) and “Sing, Sing a New Song to the Lord God” (Psalm 98), which praises God as a righteous judge. The widow in the parable cries to God about injustice, so the time of confession and assurance included laments based on Psalm 5—“Pelas dores deste mundo/For the Troubles and the Sufferings of the World,” sung in Portuguese and English, and “Lead Me, Lord.”

If Powery had preached the parable as a story of faithful prayer, then “Lord, Listen to Your Children Praying” would have been a natural response. But he said in his sermon that the parable could be called “The Parable of the Persistent God,” because God is “always willing to grant justice and give answers despite faint-hearted faith.” That made “There’s a Wideness in God’s Mercy” a better response.

“Framing is so important. It’s great if in one sentence you can make more explicit how a song connects to worship. Yet there can be resentment or lack of authenticity if we’re too didactic and explain everything.

“We need to be clear about what we want a song to do. If we want the congregation to respond in prayer or praise to God or in voice commitment or to confess after a Good Samaritan sermon, then a hymn that retells that parable, such as “They Asked, ‘Who’s My Neighbor,’ ” might be too limiting. But you could allow it to stand in place of a brief sermon, especially in a short chapel service,” Tel says.

Your congregation’s musical canon

He notes that the most important resource for choosing music is the canon or repertoire of psalms, hymns, and songs that your congregation knows and likes or loves. “Amazing Grace,” the best-known hymn in the English-speaking world, is elastic enough to fit many parables.

“If your sung responses to the proclamation in worship are not in touch with what the congregation knows, it will enfeeble all your efforts at preached proclamation,” Tel cautions.

Rather than constantly introducing new songs, ask a perceptive church member to help you identify which of the congregation’s heart songs work well for praise, confession, lament, petition, and so on. “If there are gaps, fill them. Find a song and rehearse it enough so you can use it when needed. Maybe Psalm 5 could become your congregation’s go-to song in distress,” Tel says.

The preacher can insert phrases from the congregation’s shared storehouse to shed light on other facets of a parable.

Before his symposium sermon, Luke Powery began his prayer for illumination with words from “Lift Every Voice,” words that Joseph Lowery had used a week earlier in his inaugural benediction for Barack Obama. While preaching about how hard it is to pray and get no answers, Powery used the phrase “My God, why have you forsaken me?” In explaining how we’d all lose faith if faith was up to us, he sang the words “My faith looks up to thee, thou Lamb of Calvary.”

LEARN MORE

Give yourself a free crash course in parables by reading the Parables issue of Baylor University’s Christian Ethics series. It includes six study guides, the lost coin parable service by Mark Moeller, and Moeller’s hymn “Christ’s Parables.”

Martin Tel recommends these tips for finding psalms, hymns, and songs for parable-based worship—within and beyond your congregation’s musical canon:

- “Start with a good hymnal, because it is an anthology.”

- Consult Hymns for the Gospels (GIA), which is keyed to the Revised Common Lectionary, and Singing the New Testament (Faith Alive Christian Resources).

- Do word searches on www.hymnary.org or another electronic resource, such as the CD for The Presbyterian Hymnal.

- “Two licensing agencies, CCLI and OneLicense, give you access to 95 percent of most hymnals and contemporary songs.”

Download an excerpt from And Jesus Said: Parables in Song, a collection of 55 hymns on the parables of Jesus. CyberHymnal pairs scriptural allusions with public domain hymns. You can also search the Hymnary Scripture Song Database. Use this list of online sound libraries to hear hymn tunes.

At the 2009 Calvin Symposium on Worship, all six services were based on parables. You can listen to sermons and worship excerpts and study the order of worship to see how each service flowed. View the related Prodigal Son art exhibit online or host the traveling exhibit at your church.

With so many good biblical songs to choose from, how do you decide which to use or introduce? Here’s help from John D. Witvliet for creating a balanced musical diet of congregational song. Don’t miss these tools and insights for using music in worship.

In Living the Message: Daily Help for Living the God-Centered Life, Eugene Peterson compares parables to time bombs. The first half of his Tell It Slant: a conversation in the language of Jesus in his stories and prayers focuses on the parables in Luke. In this February 2005 interview, Peterson explains what we can learn about living out our faith from the way Jesus uses language.

Include brief film clips from Modern Parables or Kenneth E. Bailey in parable-based worship.

Get new perspectives on parables in A Rabbi Looks at Jesus’ Parables by Frank Stern; Kingdom, Grace, Judgment: Paradox, Outrage, and Vindication in the Parables of Jesus by Robert Farrar Capon; Parables for Preachers by Barbara E. Reid.

Use ideas from Reformed Worship stories on parables.

Browse related stories on Bible commentaries, Eugene Peterson, “in between” words, Kenneth E. Bailey, planning contemporary worship, and worship drama.

START A DISCUSSION

Talk about seeing more deeply into parables.

- Describe a worship service or other life experience that helped you understand and live a parable in a new way.

- Jesus left questions hanging in parables. Does the older brother join the party? What ultimately happens to weeds growing with wheat or seed sown on rocky ground? How do you map those questions onto your life?

- What fears, anxieties, or concerns do you have when Christians urge each other to “live the questions” or “enter God’s story” or “remember that conversion is a process, not an event”?

- Which first steps might you like to make in having worship leaders, musicians, and preachers work together to plan parable-based worship that fits together better?

SHARE YOUR WISDOM

What is the best way you’ve found to “enter the story” of the parables?

- Did you find a simple multisensory element that helped open up a parable for your congregation? What new insights did it lead to?

- Which resources—music, visuals, video, liturgical, online, conferences, whatever—have you found especially helpful in planning parable-based worship?