Light and dark. Apple, fig leaf, ark, rainbow. Star, cross, 153 fish.

Taste and see that God is good. Abram, Jacob, Samuel, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Paul, and John—all vision struck. The Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his

glory.

Linen garments, branched candlesticks, curtains embroidered with cherubim. Stone, cedar, cypress, gold.

Soaring arches, stained glass, mosaic floors. Icons, robes, vestments, candles. Stencils on rice paper, catechetical posters, Holy Week processionals, images flickering across big screens.

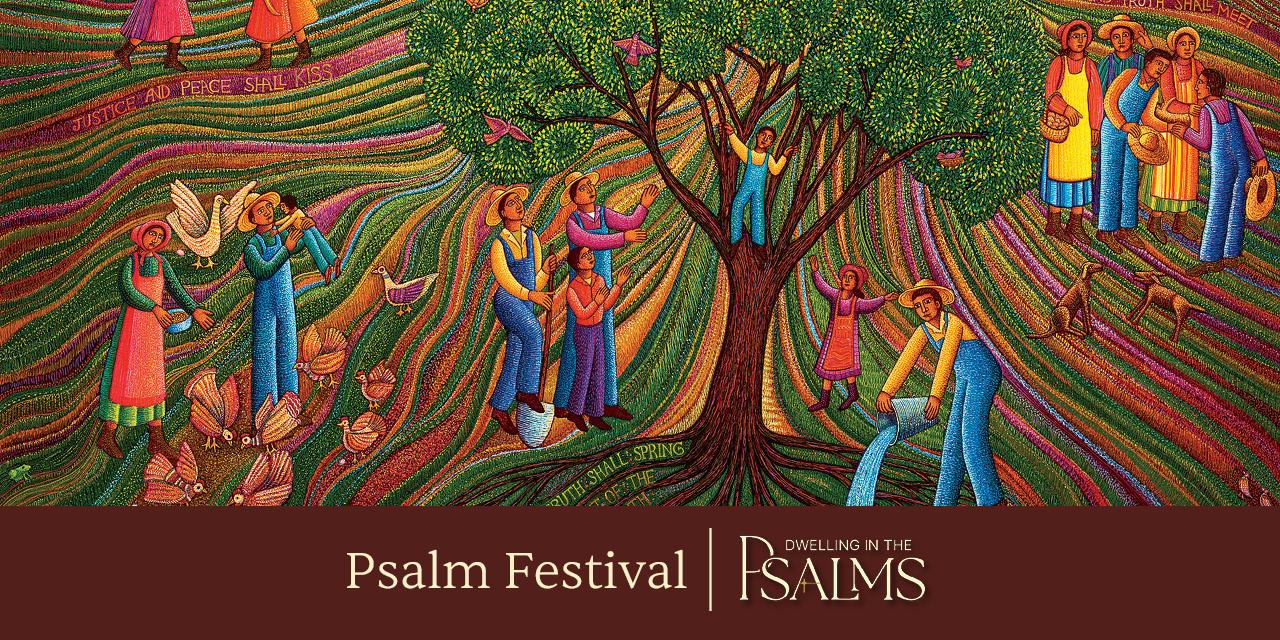

Christians around the world have different ways of using visual arts in worship. Yet we worship the same Potter, who through the indwelling Spirit shapes us to become more like Christ Incarnate.

And as lush or austere as your own visual tradition may be, you can worship more deeply by considering why and how other Christians receive God’s revelation through what they see.

Back when art was art

Opening yourself to new experiences of art in worship starts with questioning two assumptions.

First, many Christians value the verbal over the visual. We understand how the Holy Spirit uses the Bible, inspired preaching, and music to connect us with God. But linking art with worship stirs worries about idolatry, distraction, and poor stewardship.

Second, many of us think of art as something to look at in museums and galleries—something different thancraft, which is beautiful and useful.

God’s people have not always looked on art as an inferior (or impossible) way for the Holy Spirit to mediate God’s love to us. Nor have God’s people always seen art as disconnected from real life, which includes true worship.

God inspired artists to create a splendid tabernacle and temple. Jesus compared his crucifixion to the bronze serpent Moses made, a visual symbol of claiming God’s help through faith. He commanded believers to see themselves as one body in him and to experience this truth through table, bread, and wine, not just words.

For centuries, Christians offered gifts of imagination in the form of church furnishings, pageant props, sculptures, paintings, textiles, illustrated Bibles, and icons, which Orthodox Christians describe as “windows to heaven.”

The Protestant Reformers emphasized that believers can understand the Bible on their own and go to God directly through Christ. They got rid of most church art for fear people would pray to a saint rather than to God or would worship an image or its artist instead of the Creator. They believed visually stark worship spaces help Christians focus on the Bible and sermon.

Outside church walls, even Protestants continued to appreciate well-made objects, whether pictures or pitchers. Protestant artists often created art for or about ordinary life, while Catholic artists stuck to religious themes.

During the 18th century Age of Enlightenment, art became further separated not only from the church but from ordinary life. Art academies, critics, journals, and museums created a split between what philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff calls the “institution of high art” and craft. Fine art became narrowly defined as a special process of individual expression meant for aesthetic contemplation. This raises the danger of making art a religion.

Shalom and fittingness

In his classic Art in Action: Toward a Christian Aesthetic, Wolterstorff calls Christians “to extricate ourselves from the parochialism…of high art…and consider afresh…the role of art in the liturgy of the church.”

He proposes seeing “art as an instrument and object of action.” He explains that a worship liturgy is a dialogue between God and people. Within this dialogue, liturgical art can create a setting (banners, projected images) andgenerate actions (people walk forward to put checks and cash in colorful porcelain bowl) that serve a liturgical purpose (offering thanks to God).

Wolterstorff describes both art and liturgy as social practices. When he wrote Art in Action, he believed art used in worship should serve the liturgy. “Now I think that that is too simplistic. There needs to be a negotiation in which neither the practice of liturgy nor the practices of art ‘call the shots,’ ” he says.

Cautioning against an exuberant mix-and-match, Wolterstorff says that liturgical art must fit the congregation’s self-understanding and the artistic elements must form a whole.

The liturgical year shapes how people understand themselves at Church of the Servant Christian Reformed Church in Grand Rapids, Michigan. During Epiphany they look with new eyes for Jesus, the light of the world. The Epiphany Eyes banner and other visual elements convey this theme. References to light and sight pepper the Epiphany liturgy and songs.

Wolterstorff says art is a way of showing, as no other activity can, something about the world’s depth and reality. Artists create possible worlds that help people envision (or rebel against) the final shalom God will create when Christ returns to completely renew creation.

Looking at the world through this creation-fall-redemption-renewal pattern makes every liturgy’s final section—the sending—especially important. Renewed in worship, Christians go back into daily life to bring about shalom, according to how God has gifted them.

Artistic actions and results

Still convinced that art is mainly for looking at? Lisa DeBoer, a Westmont College art professor, lists many more roles for art, each appropriate for worship: “Art can create identity. Art can define space. Art can dramatize the parts of worship. Art can interpret the sacraments. Art can shape movement. Art can mark time. Art can anchor memory.”

Besides broadening art’s role beyond contemplation, DeBoer urges artists to think beyond individual self expression. While working with student artists in worship renewal projects, she discovered it’s crucial to help artists define and discuss their unspoken assumptions about art.

She also discovered a model that can work well in churches. She paired each artist with a group of non-artist friends for a Stations of Christ’s Life project. Group members read and prayed through the biblical narrative relevant to “their” part of Christ’s life. Each artist consulted with his or her group on how to create a work that others could understand and appreciate. Artists also met weekly with each other.

“This formula proved extremely successful,” DeBoer says. While supporting and pushing the artists in new creative directions, the non-artists began to appreciate the artistic process and came to love the art. The artists learned the joy of creating something for a community.

Learn More

This visual arts resource directory includes downloadable images, artists’ websites, and art events. Find images keyed to the lectionary. Browse dozens of websites about Christian modern art, including A Broken Beauty.

Learn the story behind biblical and Christian symbols in Elizabeth Steele Halstead’s new Visuals for Worship, which includes downloadable images on CD. It’s designed as a companion to The Worship Sourcebook.

Enrich your syllabi. Sing songs celebrating the arts.

Evaluate the risks and rewards of using more art. Read this Lutheran Church of Australia statement on the purpose of visual arts in worship. Then consider writing an arts purpose statement for your congregation.

Form a visual faith discussion group. Start with an essay or conference presentation. Graduate to good books on Christians and art, including some from Lisa DeBoer’s annotated list.

Write book reviews and donate books to your church library:

- Art in Action: Toward a Christian Aesthetic by Nicholas Wolterstorff

- Reformed Theology and Visual Culture: The Protestant Imagination from Calvin to Edwards by William Dyrness

- Toward a Theology of Beauty by John Navone

- Visual Faith: Art, Theology, and Worship in Dialogue by William Dyrness

- When Church Became Theatre: The Transformation of Evangelical Architecture and Worship in Nineteenth-Century America by Jeanne Halgren Kilde

Congregational Resource Guide recommends several resources on art, architecture, and worship, including Church Architecture Network, Built of Living Stones: Art, Architecture, and Worship, which gives guidelines for renovating or building Catholic churches, and Patricia S. Klein’s Worship Without Words: The Signs and Symbols of Our Faith.

Browse related stories on art that preaches, church renovation, and how congregations are incorporating visual art.

Start a Discussion

- So often we make sense of life by thinking in polarities—visual, verbal; know and do, see and love; shalom, Shabbat; action, contemplation; worship, discipleship. Regarding visual art in worship, which polarities are at work in your congregation?

- Brainstorm about new ways to experience art in worship. What risks and rewards do you see?

- Would you say that visual art in your church is more solid (permanent part of building), seasonal (perhaps keyed to Christian year), or ephemeral (here one week, gone the next)? What does this tell worshipers about your theology?

- How has your congregation—in its worship and ministries—addressed the cultural shift from print and verbal communication to visual communication?

- What do you think of the claim that contemplation is (or should be) central to biblical spirituality and Christian worship?

Share Your Wisdom

What is the best way you’ve found to explore visual arts in worship?

- Did you develop a template or checklist to help young people visit other churches and note differences in how visual art is used?

- What has worked best—or not worked well—in your efforts to use visual art as an evangelistic tool?

- Which resources or strategies have helped people work together to create art for worship? Which questions have helped the artists and non-artists among you air their unspoken convictions about what counts as art and how it should be used in worship?