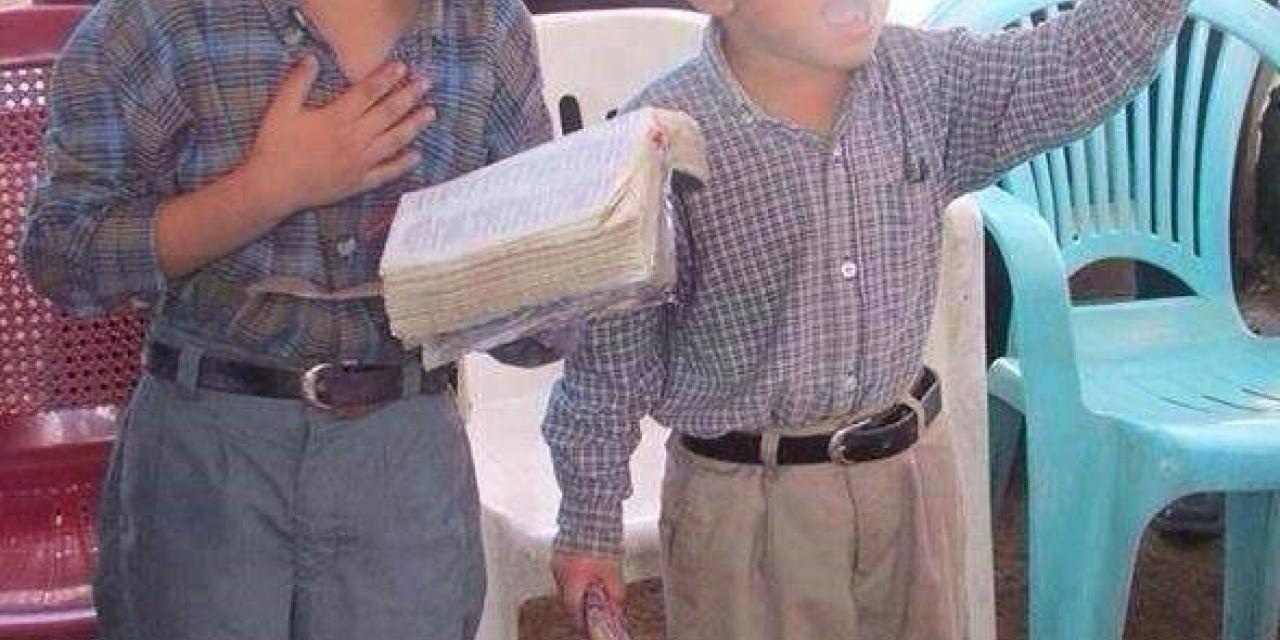

The photo speaks a thousand words about pure, simple, heartfelt and childlike worship.

Someone commented on the tattered condition of the boys’ Bible—“That book is being used!” Another commented, “Dirt floors, plastic chairs, but hungry hearts for God. So responsive to the Holy Spirit. Such pure worship. It can teach many of us what worshiping the Father in Spirit and in truth really means. Coming to the Father as a child...humble...trusting...expectant.”

Music has had a great role to play in every society and culture throughout history. It is mentioned already in Genesis 4 in the Bible. Israel’s history is full of music and poetry in psalms and songs, including dance, like the Jewish festival of Simchat Torah (“Dancing with the Word of God”) still celebrated each year. Music has always been part of the Christian church as well; the Apostle Paul encouraged the singing of psalms and hymns and spiritual songs (Ephesians 5:19, Colossians 3:16). And the history of Western civilization is filled with a rich tradition of music based on scripture and Christian liturgy.

In contrast, all music in Muslim worship is banned, whether vocal or instrumental. Yet there is a role for music in Muslim culture in spiritual inspiration, for example in Sufi dance and Qawalli song. For several years I taught music in a large Muslim girl’s school in Karachi, Pakistan. During those years I attended a workshop organized by the Aga Khan education board on the “Role of Music in Montessori Curriculum.” The most significant learning for me came from the workshop leader who was trained in the UK and ran a Montessori training center for teachers in Pakistan. Along with Montessori teachers from across Karachi, she invited Muslim clerics to the workshop, because she was struggling to find avenues to use the powerful medium of music to educate young children. She invited those Muslim clerics to find Islamic jurisprudence on the role of music in education.

This year, while studying at Calvin College and Calvin Theological Seminary, I have been breathing in music and theology in a number of ways. The annual Fall Music Festival at Calvin College was a particularly remarkable experience, one where theology and music flowed together. Different ensembles offered stunning and breathtaking presentations of different genres of music—the Orchestra, Women’s Chorale, Campus Choir, Gospel Choir, Symphonic Band, Capella, the Wind Ensemble, and combined forces when all the choirs sang together accompanied by the orchestra.

There was a sense of community, service and faith expressed through music for the glory of God. Conductors were full of passion, energy and pride in their students, and commitment to the purpose of making music in service to God and the people of God. It was performance, of course, but performance with purpose—to educate and encourage students, to produce musicians with artistic skills, preparing them for serving both God and society. Theology, music and community flowed together. The music was not liturgical, as for a worship service, yet there was worship in and through these performances.

Especially since the Enlightenment, there has been a growing divide between the sacred and secular, also with respect to music. But lately, the pendulum has swung back to embrace the broader culture within the church. It is difficult to separate music in the church from music in the culture. There is much emphasis in contemporary culture on entertainment and a “show” mentality. That mentality is often found in contemporary church life as well. But true, honest and pure worship can’t be bought with worldly richness. For centuries, the church influenced the culture. But today, culture greatly shapes and influences music for worship, especially in Protestant worship. Here are a few observations of ways contemporary culture has affected Christian worship:.

- We want to be in control, independent, singing songs that satisfy personal preferences; we are not particularly interested in being challenged to change.

- We are accustomed to self-worship and try to hide our flaws, weakness and sins behind the “all is well” mask. We resist songs that emphasize our utter need of God; we tend towards becoming igods,

- Many resist worship songs that challenge our self-centeredness in order to be transformed to the image of Jesus Christ, where we decrease so he can increase (John 3:30), bringing every thought into captivity to the obedience of Christ (2 Corinthians 10:5).

- We exchange the church platform where God’s Word is proclaimed for a stage where performers sing for audiences.

- We want excellence in music performance, but only in others, since we are not challenged to sing as much as to listen. We become an audience rather than participants.

These observations cause questions about the relationship between the roles and goals of music in culture and worship.

- Can technology interfere with honest and deep worship in Spirit and truth?

- Should worship music serve to entertain (horizontal), or to enact a covenantal (vertical) relationship with the triune God?

- How needed are high technology, lightshows, or even instruments for true worship?

- Does weekly communal worship enable us to walk daily with God or do we attend in order to enjoy and applaud a good religious show?

- Does our worship attract others to stand beside us and worship his majesty?

There is a different role and purpose for music in worship than in society. We need to remember that worship is about God, not about us.