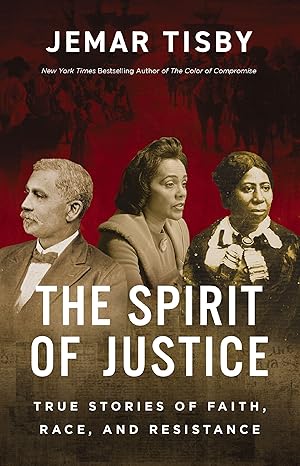

Jemar Tisby is a historian, author, and speaker who teaches history at Simmons College of Kentucky, a historically Black college or university (HBCU) in Louisville, Kentucky. He taught sixth grade in the Mississippi Delta and was a middle school principal before earning his MDiv from Reformed Theological Seminary. His doctorate in American history from the University of Mississippi focused on the intersections of race and religion in modern US history. In this edited conversation, Jemar Tisby discusses his book The Spirit of Justice: True Stories of Faith, Race, and Resistance.

Jemar Tisby is a historian, author, and speaker who teaches history at Simmons College of Kentucky, a historically Black college or university (HBCU) in Louisville, Kentucky. He taught sixth grade in the Mississippi Delta and was a middle school principal before earning his MDiv from Reformed Theological Seminary. His doctorate in American history from the University of Mississippi focused on the intersections of race and religion in modern US history. In this edited conversation, Jemar Tisby discusses his book The Spirit of Justice: True Stories of Faith, Race, and Resistance.

Who are your primary and secondary audiences for The Spirit of Justice?

This book is primarily dedicated to those of all races who are weary and heavy-laden from pursuing racial justice. The secondary audience is everyday Christians who have found themselves estranged from their faith community because of unhelpful stances on race. I hope this book will give them courage to take whatever next step God leads them to take.

How do you explain the spirit of justice to someone who hasn’t thought about it?

The spirit of justice is the fingerprint of God on all souls that says we are made for dignity and freedom. This spirit rises up inside of us to help us say, “This is not right.” For Christians, we can also think of this as the Holy Spirit leading us into actions aligned with God’s heart.

The spirit of justice is the fingerprint of God on all souls that says we are made for dignity and freedom.

The spirit of justice opposes what the King James Version of the Bible calls “the powers and principalities” and other Bible versions translate as “rulers and authorities,” “forces and authorities,” and “rulers and powers.” White supremacy is a demonic power and principality—an ideology that stands against the spiritual powers of love, dignity, and respect. Even in white Christianity, we are seeing the rise of this movement that greatly narrows the idea of who even counts as a human.

What lesser-known profiles were you especially pleased to include in this book?

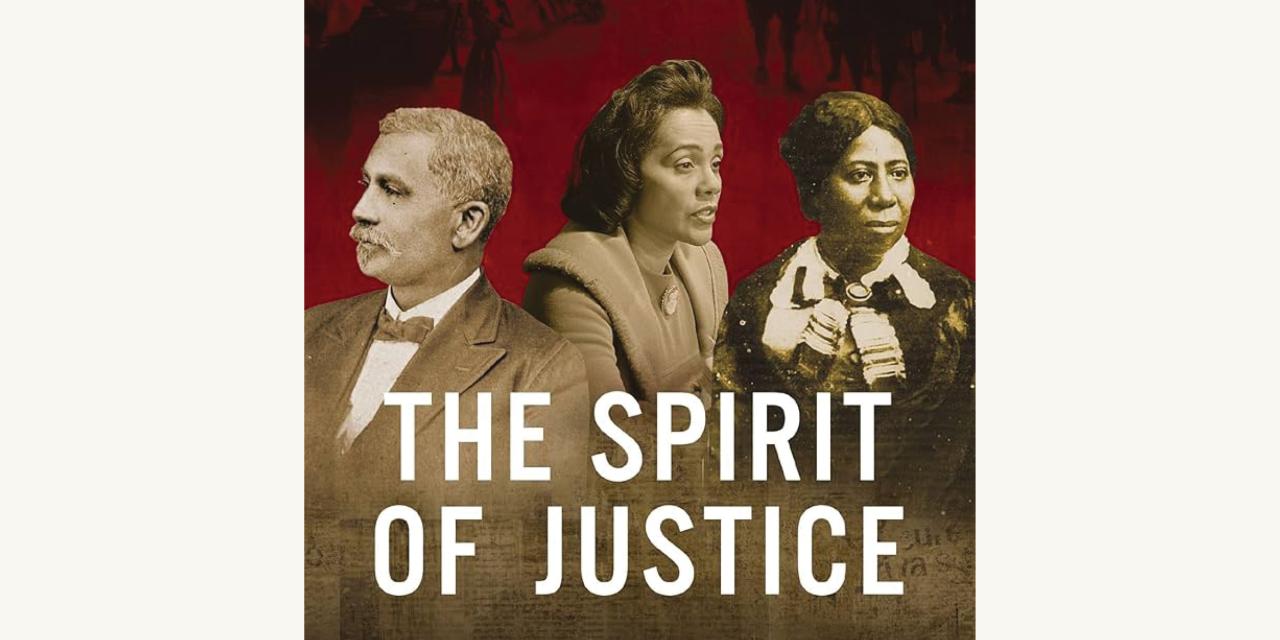

I was so glad to include E. C. Morris on the cover. Almost no one recognizes his face, but he was born enslaved in Georgia in 1855 yet managed to attain a college education. Rev. Morris was the first president of the National Baptist Convention, a historically African American denomination, from 1895–1922. He was based in Helena, Arkansas, where I grew up. Helena is about an hour south of Memphis, Tennessee.

I was so glad to include E. C. Morris on the cover. Almost no one recognizes his face, but he was born enslaved in Georgia in 1855 yet managed to attain a college education. Rev. Morris was the first president of the National Baptist Convention, a historically African American denomination, from 1895–1922. He was based in Helena, Arkansas, where I grew up. Helena is about an hour south of Memphis, Tennessee.

Morris pastored Centennial Baptist Church, which had stained glass windows in a beautiful red-brick building by a Black architect. Morris established a publishing house to create materials for Black Baptists and developed a national presence. He shepherded his people to uplift themselves through business, education, the church, and organizational leadership.

And another lesser-known profile?

I liked doing a different take on people we already know of. Most people know about Frederick Douglass, an abolitionist who led the civil rights movement in the 1800s. I chose to profile his wife, Anna Murray Douglass, who is on the right side of the book cover. She is truly an unheralded hero because without her, Frederick Douglass could never have become what he did. Anna was born free in Baltimore and met Frederick while he was still enslaved.

Anna helped him escape from slavery by sewing him a sailor’s uniform, borrowing a freedman’s identification, and providing money for them to start a new life in Massachusetts. She used her gifts in organization, management, and saving money to run the household, support Frederick’s speaking trips, and harbor fugitives on the Underground Railroad.

Had you known about all these champions for justice before you wrote The Spirit of Justice?

I knew most of them by name, but sometimes you read about one person and follow references to another. Queen Nanny of Jamaica, whom I profiled in the second chapter, was new to me. She used her skills in guerilla warfare to help her community of people who’d escaped enslavement to defend themselves against the British and remain free.

Nor had I known about H. Ford Douglas, whom I wrote about in the fifth chapter. He used his light skin privilege to pass as white so he could enlist in the Union Army and fight for Black freedom. When the Emancipation Proclamation legally allowed Black soldiers to join the military, he requested to be transferred to an all-Black unit. He was also a preacher who rooted his antislavery activity and military service in a deep understanding of the image of God in Black people. He criticized the hypocrisy of white Christians who professed to follow Christ while supporting slavery.

What do you hope that non-Black people will learn from The Spirit of Justice?

I hope they will learn that the Black Christian tradition is part of their spiritual family tree. All the people I profiled had flaws, but their stories give us all something to draw on and emulate. These brothers and sisters in Christ give us a narrative history to counter white supremacy. When I started researching this book in 2020, I had hoped it wouldn’t be quite as relevant as it is today.

The Black church has a lot of experience with society and government being against them. As more and more people today are marginalized and cast aside, it helps to hear how other Christians have kept the faith. The same spirit of justice that inspired them is alive and active today in each one of us who refuses to quit imagining the world that the Prophets and God intend. As in 1 Corinthians 12, I hope readers see that we each have unique experiences and gifts that God can use in working toward the common good.

Do you have any advice on talking about injustice with children of different ages?

I just light up when I can talk about the spirit of justice with children and youth. That’s why I’ve sought out collaborators to help share the message in developmentally age-appropriate ways. I Am the Spirit of Justice is a picture book for children aged four to seven or eight. I wrote this with my childhood best friend, Malcolm Newsome, and Nadia Fisher illustrated it. Kids often ask, “Why did white people treat Black people so badly?” Their confusion reminds us as adults how truly nonsensical this is.

I wrote Stories of the Spirit of Justice for ages eight to twelve. Many books focus on one person, like Martin Luther King Jr. or Rosa Parks. This book divides stories into historical eras, so readers get a sweeping view of people who worked for racial justice in the US, including some white people. Each story is paired with a tip for how readers can live out the spirit of justice.

When and how should churches use these stories in worship services?

When to talk about it is now. People are lamenting and grieving unjust changes in our country. If we don’t allow that grief and lament in worship, it impedes our ability to resist injustice. For example, I think we should have a national day of mourning for the millions of people who died of COVID. If we don’t disciple people in church to talk about examples of denying the image of God in certain people, then we are not obeying the Holy Spirit’s call to work for justice.

How to do this starts with what a pastor studies and teaches, because this reflects to the congregation what they should value. If you only quote white males, that gives a message about which voices matter most. So maybe it’s time to diversify your bookshelves. Pastors truly do need to educate their congregations about public justice and how to talk about it in the public realm. We shouldn’t abdicate that responsibility. The current situation is not business as usual, so churches can’t be business as usual either.

What’s a specific example of working for justice that ordinary Christians can do?

I do a weekly email magazine, The Convocation, with fellow Substack writers Diana Butler Bass, Kristen Kobes DuMez, and Robert P. Jones. We recognize that there can be costs when pastors preach about justice. Diana went to her pastor and said, “If anyone in this congregation threatens to withdraw tithes and offerings, I will make up for that by increasing my giving.” Sacrifice is something anyone can do, though we can’t all give the same amount. We need to gather around truth tellers and proclaimers to care for them and demonstrate our love.

Learn More

Read about Jemar Tisby’s detailed bio and faith journey on his website. Gather a group to read and discuss The Spirit of Justice: True Stories of Faith, Race, and Resistance, The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism, or any of his other books for adults and youth.