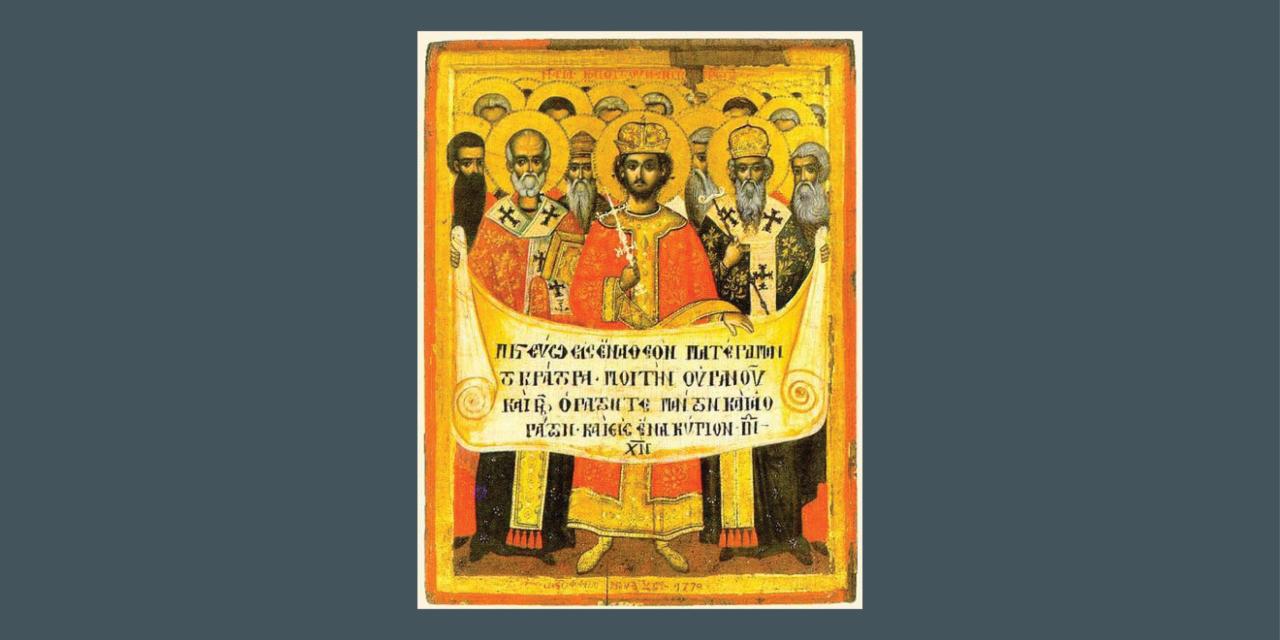

“A little over an hour into Ron Howard’s cinematic adaptation of The DaVinci Code, for the first time in a major Hollywood film we see a portrayal of the Council of Nicaea.” That’s how Young Richard Kim introduces The Cambridge Companion to the Council of Nicaea, a 2020 book he edited.

“The DaVinci Code is kind of dated now,” says Kim, who teaches classics and ancient Mediterranean history at the University of Illinois Chicago, “but it’s a page turner, full of conspiracies. One is that in 325 A.D. the Council of Nicaea, under the direction of the emperor Constantine, decided that Jesus was divine. Novelist Dan Brown said this declaration was meant to hide the fact that Jesus had a family with Mary Magdalene. So this view sees the Nicene Creed as a suppression of truth about Jesus Christ.”

“The Nicene Creed is an extraordinary document that some Christians are very used to using in worship. Others don’t know what it is—or are even antagonistic to it because they believe it goes beyond what the Bible says,” explains Beth Felker Jones, who wrote Practicing Christian Doctrine and teaches theology at Northern Seminary in suburban Chicago.

Notre Dame University theology professor Kimberly Belcher admits: “It’s kind of hard work to get people to care about the Nicene Creed.”

Yet all three scholars share the optimism of Jerry Pillay, general secretary of the World Council of Churches. He said that recognizing the Creed’s significance can help global Christians renew the church’s call to demonstrate “a unity that is visible and tangible, reflecting the oneness of the body of Christ.” He sees this anniversary as a stepping stone to the “significant year of 2033—a year that marks the two-millennial celebration of Christ’s resurrection. Being a part of this journey is essential, as it is a journey that calls for our active participation and commitment to the unity and witness of the church,” he said.

“We believe . . .”

Young Richard Kim explains that in the early fourth century, Christianity was a persecuted minority religion. Emperor Constantine is said to have converted to Christianity in 312, and in 313 he issued the Edict of Milan, in which he declared that all Romans would have freedom of religion, thus decriminalizing Christianity.

“Historians disagree on how sincere or authentic Constantine’s conversion was, but they agree he became a patron of the church and saw Christianity as a way of unifying his empire,” Kim says. “This alignment with government set in motion a completely different direction for Christianity. I think there are problems when the apparatus of the state dictates what churches are doing—and vice versa.”

Meanwhile, controversies arose among competing Christian beliefs. Arius, a Libyan-born priest of a church near Alexandria, Egypt, concluded that Jesus was not divine and coeternal with God the Father but was instead created by the Father. The Bishop of Alexandria and Athanasius, the bishop’s secretary, said Arius was heretical. They argued that if Jesus is “like” but not of the same substance as the Father, then he cannot be Lord and Savior.

“We throw around terms like ‘heresy’ and ‘orthodoxy’ too easily,” Kim says. “Often a lust for power is behind this. Arius wasn’t an evil guy. He held onto the singularity of God the Father because studying the Bible gave him a very high view of God. Constantine thought this simmering debate was petty, but he didn’t want his new religion to be a house divided. So he called and convened bishops, presbyters, and deacons in the empire to gather in Nicaea, the modern Turkish city of Iznik.”

More than 300 people, including Arius and a young Athanasius, met from May through July in 325. They decided that the Father and Son are homoousios (of the same substance), a word that doesn’t appear in the New Testament. Kim notes that the meaning of this Greek philosophical word is vague, so bishops with competing ideas were able to agree with it.

“In 350, people started talking about the Holy Spirit,” Kim says. “The 381 Council of Constantinople added theological language about how the Holy Spirit is equally part of the Godhead. The Nicene Creed we recite today is actually the Niceno-Constantinople creed.

“The ancient creeds were used mainly as a summary to teach candidates for baptism. The Nicene Creed is also used in worship during communion. Later church councils dealt with new questions, such as how Jesus is [both] fully human and fully divine. The Nicene Creed is not comprehensive, not meant to express and explain everything. It gives trinitarian boundaries for our understanding of God. The lesson for us,” Kim explains, “is to accept mystery and avoid the abuse that can emerge from fixation on our own theological rightness. We can share fellowship and communion with Trinitarian Christians from many traditions. We can follow a way of love that makes room for different ideas.”

Relevant for today

Felker Jones explains that the point of the Nicene Creed is to introduce us to the trinitarian God. “This ecumenical summary of faith and biblical witness has stood the test of time,” she says. “Its language is simple, yet complex, and beautifully points us to the glory of God.”

For example, the section about Jesus begins:

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father;

through him all things were made.

“The Nicene Creed is relevant now because God’s nature and character are being contested,” Felker Jones says. “People disagree on whether God is all about authoritarian, top-down power, or [whether] God is love. In 325, Arius couldn’t imagine that the Son and Spirit could be truly God, because he couldn’t imagine that God the Father would share his power. But the Nicene Creed says that the three persons of the Trinity can be coeternal, coequal in love, power, knowledge, justice, and so on. This model of an eternally self-giving ‘Tri-unity’ can be an antidote to human pride.

“We don’t have to know all the theological details of the Trinity to let the Nicene Creed form our life and worship,” she says. “I’m a big fan of reciting the Nicene Creed in worship, acknowledging the Trinity in prayers, and singing trinitarian hymns. If your church is traditionally noncreedal, you can still use the Nicene Creed as an educational tool because it expresses the Bible so well. It is one of the best evangelical and ecumenical documents we have that holds together churches across time and space—[but] we’re talking about most churches, not all. Some evangelical churches teach that Jesus is secondary to the Father, partly so they can enforce gender roles.”

Felker Jones says she dreams of how celebrating the 1,700th anniversary of the Nicene Creed might call Christians around the world to worship and praise the one holy, triune God. “Enthusiasm for the creed builds enthusiasm for Jesus Christ,” she explains. “It can inspire us to know the Scriptures more and learn about how Christians in different eras and places have understood and lived out the Scriptures.”

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, eternally begotten of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, of one Being with the Father; through him all things were made.

Receptive ecumenism

Belcher says that because Catholics recite the Nicene Creed every Sunday in response to the gospel reading, the familiarity of the words can keep people them from thinking deeply about them. She hopes that paying more attention to the Nicene Creed during its 1,700th anniversary can promote receptive ecumenism and “prioritize the flourishing of unity throughout Christian churches.”

Belcher defines “receptive ecumenism” as “focusing on being able to recognize one another’s ways of being Christian through my own formation of being Christian. When I recognize Jesus’ life in your Christian practice, then I am answering the call Jesus gave in John 17 for us to be one as he and the Father are one.” Her book Eucharist and Receptive Ecumenism: From Thanksgiving to Communion describes vast differences in eucharistic practices, yet all who celebrate communion and the Lord’s Supper are, at the core, giving thanks to the Father for God’s covenant with us and the world.

Likewise, even though translations of the Nicene Creed vary, its 1,700th anniversary can prompt us to reflect on unity. The Nicene Creed is more widely accepted by Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and major Protestant churches than the Apostles’ Creed and Athanasian Creed are. But Orthodox versions of the Nicene Creed do not include the Filioque clause, which states that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son. This addition to the creed is partly why the Eastern Orthodox Church split from the western Catholic Church in 1054.

“Almost any time I’m in ecumenical spaces, we Catholics and Protestants show unity with Orthodox Christians by omitting the filioque,” Belcher says. “We don’t see this difference in verbal expression as more important than acknowledging our oneness in Christ.”

Belcher hopes the creed’s anniversary will prompt more people to think about what it means to believe in “the Father, the Maker of heaven and earth,” “one Lord, Jesus Christ . . . through whom all things were made,” and “the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life.”

“I hope that paying attention to those phrases will help people see all creation as God’s beloved creation, not just humans,” she says.

There’s a movement among many Christian traditions to institute a Creation Day Feast to highlight God’s activity in creation.

“At a Laudate Si’ Research Institute event in Assisi, Italy, Christians from the Global South were especially interested in a feast that attends to God’s work as Creator,” Belcher says. “They are more exposed to radical shifts because of climate change. Some from the Global North tend to emphasize human control over the environment and felt ambiguous about why it’s so important to focus on God’s role in creation over other issues. But it’s evident to those in the Global South that all the positive and negative things we might bring to God [such as health, economies, migration, and war] are related to climate change.”

Belcher’s big dream about living out the Nicene Creed is that “each church will learn to prioritize other churches’ flourishing. We can appreciate diversity without becoming divisive, seeking to be united in holiness and the will of God. In his inaugural address, Pope Leo XIV said the risen Christ calls us to a ‘disarmed and disarming peace, humble and persevering.’ Remembering that the Nicene Creed is an

enduring document that almost all Christians hold in common, we can recognize differences in how we live with God without weaponizing those differences.”

Learn More

Learn more about why the emperor Constantine chose to call Christian bishops, presbyters, and deacons to Nicaea.

Check out Public Worship and the Christian Life podcasts about the 1,700th anniversary of the Nicene Creed:

- Jared Ortiz on the Dramatic Nature of the Nicene Creed

- Jane Williams on the Nicene Creed as a Creative and Exciting Description of Who God Is

- María Eugenia Cornou and Mikie Roberts on the Doxological and Historical Significance of the Nicene Creed

Note differences among English-language Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox versions of the Nicene Creed. Many Protestant churches use the 1988 version created by the English Language Liturgical Consultation.

Reformed Worship has several free articles related to the Nicene Creed. It gives suggestions for worship and music, activities, a responsive reading, and notes why it still matters to include creeds in worship.

Consider using theologian N. T. Wright’s “The Prayer of the Trinity” and fifteenth-century Russian painter Andrei Rublev’s famous icon The Trinity. The icon shows the communion of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit and leaves space at the table to symbolize how the Trinity invites us to join in praise, worship, and service.

June 8, 2025, were rare Sundays because Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox Christians all celebrated Easter and Pentecost on the same days. The Orthodox calendar calculates the date of Easter each year differently than Catholics and Protestants do, so the Orthodox Easter celebration usually falls on a different date. The World Council of Churches has been advocating a common Easter date for all three major Christian branches. Doing so would be a visible witness of Christian hope and unity.

Among many Nicene Creed 1,700th anniversary events, the most important may be the Sixth World Conference on Faith and Order, held October 24–28, 2025, in an ancient Coptic Orthodox monastery near Alexandria, Egypt. The World Council of Churches chose the theme “Where now for visible unity?” because the world needs ecumenical unity. “A world of climate catastrophe, pandemic, war, and economic concern requires a fresh engagement of the churches with one another on the core issues of faith, unity, and mission that both unite and continue to divide them,” the conference website says.

Consider reading these books and reviewing them for your church library:

- The Cambridge Companion to the Council of Nicaea, by Young Richard Kim, is a scholarly collection of essays.

- Eucharist and Receptive Ecumenism: From Thanksgiving to Communion, by Kimberly Belcher, shows how to appreciate and learn from the diversity of Christian communion practices.

- Practicing Christian Doctrine: An Introduction to Thinking and Living Theologically, by Beth Felker Jones, helps Christians live what they profess by connecting each doctrine to a spiritual discipline.

- The Underwater Basilica of Nicaea: Archaeology in the Birthplace of Christian Theology, by archaeologist Mark R. Fairchild, asks whether a site discovered in 2014 might be where the First Council of Nicaea took place.

Laudate Si’ Research Instituteis promoting a new Creation Day Feast on September 1, the first day of the liturgical Season of Creation. Partners in this effort include the European Christian Environmental Network, World Communion of Reformed Churches, and World Council of Churches.